combat necrophagy

NEVER A PYGMY

chapter

three of

One Not One

|

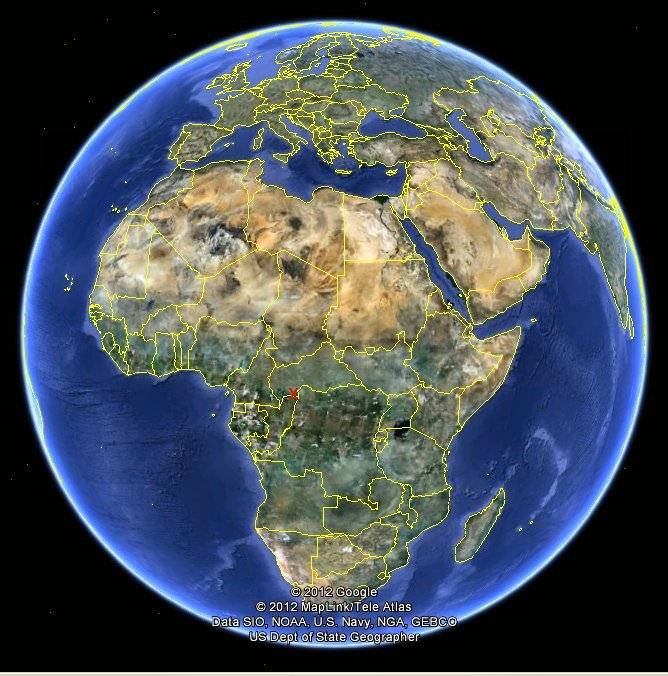

Most of my early education came from shoplifted books, and one such was Colin Turnbull's Wayward Servants: the two worlds of the African Pygmies, an academic sequel to his widely-read The Forest People, in which he recounted his time with the Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Forest of north-eastern Congo (later Zaïre, now Democratic Republic of Congo). In both books he showed how the Mbuti not only did not live in servitude to the non-Pygmy Africans who claimed them as serfs, but lived remarkably happy, healthy and harmonious lives doing pretty well what they wanted to - a bit like the admirable bonobo (or 'pygmy') chimpanzees farther to the west.

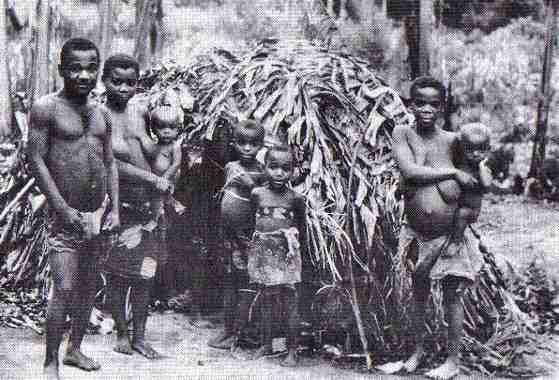

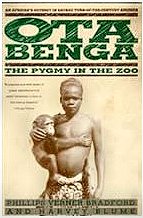

All the literature about Pygmies hitherto had described them as abject servants of the non-Pygmies who, only a few centuries ago, had, in overrunning Africa, pushed the the Pygmies into the forests that stretch between Uganda and Gabon, the 'Bushmen' into the Kalahari, and the Hottentots to the very southern tip of the continent. The small 'Pygmy' populations were in separated groups, and all were Gatherer-Hunters. Turnbull also showed that gathering provides more food than hunting, which is carried out partly for the sport and to get a bit of exercise. Their 'servitude' to settled Africans was really a loose agreement whereby the Pygmies would bring meat to the villages in return for various luxuries such as palm-beer and knives. Pygmies, like most forest people, do not like to be tied down or ordered about, and, since the agreement was largely to the villagers' benefit, they brought meat only when they felt like it. They could not be coerced, because they could simply melt into the mothering forest, which scares patriarchal, villager Africans. The Mbuti Pygmies are now on the edge of a terrible war-zone, where DR Congo abuts Sudan, Uganda and Rwanda. This is the area of war-lords, expelled Hutu, mercenary soldiers, and coltan mines. But they seem to be surviving, because they can always melt into the forest - which has not yet been trashed. Some have become truck-drivers. By the time I was seventeen, I had lost any faint will I might have had for 'a career' or 'normal' future. Never competitive, ambitious or 'aspirational', I drifted on a sub-educational conveyor-belt with as little effort as possible, from minor (and local) private school to minor university, from which I dropped out twice. I opted eventually for Philosophy, so that I could get to grips with The Meaning of Life, but was sadly disappointed. Philosophy (as Diogenes pointed out a long time ago) is not for those who wish to live a good, honest or wholesome life. Unless you are Peter Singer. When other youths of my acquaintance were seeking girlfriends and going to dances, I was reading Kafka and Dostoyevsky (amongst other metaphysical luminaries), thanks to my blatant but undetected shoplifting of Penguin Classics in the 1960s. Although I am a 'born philosopher', it seemed to me that Socrates had been a bit of a fool, Jesus the Anti-intellectual Commensual Ascetic had obviously been horribly betrayed by his fanatic followers, Kant left me cold, Spinoza seemed as smug as a black tulip, Hegel was heartlessly hieratic, and those dreary British philosophers who, typically, had no aesthetic at all about them left me bemused and depressed. In Schopenhauer I detected an unpleasantly eugenicist attitude, which paradoxically went hand in hand with his luke-warm defence of homosexuality. Nietszche I warmed to poetically, but I felt immediately that his whole philosophy was undermined by his seeking of the Übermensch, the Wonderful Other that he could not be. Freud repelled me because of his personal power-complex enshrined in his ludicrous doctrine of the Oedipus Complex. Jung attracted me greatly, but he had no real philosophy. I had not yet discovered Diogenes, who (wonderfully, and like a Pygmy) left no written text. I admired the 'extremists' - Kropotkin, Bakunin, Brecht - but their lack of anthropological awareness, their pseudo-science, and their dreadful Bolshevik legacy betrayed them. Hesse was exciting, but vapid. I read on, thanks to stolen books. Castaneda at least was vaguely anthropological, but spoke in parables even less useful than those of Jesus. The various Buddhist teachings and scriptures opened up what I might call Philosophical Feeling, but in the end compromised awareness with numbers and route-maps (three-fold paths and similar nonsense for the Normals) which turn Philosophical Feeling into Duty, its opposite. Sufi writers were hamstrung by patriarchal Islam, and ended up being downright (if poetically) obscure. I was a consciousness-in-waiting for illumination, but unfortunately (?) nothing written seemed convincing, much less useful to someone raised in the hermetic backwater, the blind cultural thralldom that was (and to a large extent still is) Ireland. So Turnbull's description of a more-or-less 'Perfect Society' of people living in undoctrinal (hence gentle) harmony with 'Nature' set my damp spirit alight. Here were people who had no formal institutions, (and certainly not the toxic institution of marriage and family) who had very simple and effective mechanisms to deal with social friction. They lived in small groups, whose composition changed over time, as people moved from one group to another. Because there was no marriage, there was no problem with paternity, and children were brought up communally. Since there was no marriage, there was no adultery. Everyone belonged to the voluntary group. Even the handicapped (very few in any group) had a social role as entertainers or musicians. But this kind of co-operative life was the opposite to the western and Israeli ideas of 'communal living', for there was no coercion to behave in any particular way, no rotas, and certainly none of that artificial sense of loyalty which is the creator of strife. If someone got up several people's noses, that person was gently encouraged to be more cohesive, or to drift off to another group. Pygmies even took account of loners, and those (usually male) who wanted to exclude themselves from the group were allowed to - but were not allowed to starve. They were very like the Amazonian Pirahã in their attitude to religion, seeing it (correctly) as coercive. and disrespectful of nature. Their whole outlook on life was anti-coercive, collaborative but not compulsorily so - and thus in stark contrast to the totalitarian values of all civilisations. I had read Tobias Schneebaum's famous (or notorious) Keep the River on your Right, so I decided I would go and see if what Turnbull said was true, and, if so, would Seek my Salvation (Buddhist, Christian) with people without the curse of religion, because I certainly could not see how to live with any kind of integrity within the culture whose doctrines of aggression, greed and hypocrisy had dominated the world and murdered millions. This part of the world had suffered particularly. There had not only been the results of the ghastly, capitalist Slave Trade which destroyed societies and economies throughout the Western part of Africa, but there had been the particularly appalling rule of Leopold I of the Belgians in his private concentration-camp, described in a very mild way by Joseph Conrad, and the kidnapping and exploitation unto death of hundreds thousands of people from Ubangi-Shari (now the Central African Republic) by the French in their little Congo (Moyen-Congo) to build the infamous railway from Brazzaville to the coast - a railway with more bridges, tunnels and embankments per kilometre than any in the world. I wrote to Colin Turnbull, and - amazingly - he wrote back, saying he would be in London in a few weeks, and I could meet him there. He had received hundreds of letters in response to The Forest People, but I was the only person to ask for help in going to join the Pygmies. We met, in London, and he straightaway took me to the last palatial Victorian Turkish Baths to remain in London. This was to see if I could tolerate the rain-forest climate. I survived the experience, but of course an hour in a steam-bath is not at all like a life in the rain-forest. He suggested that it would be a good idea for me to go and find a different group of Pygmies to find and live with: the Binga who lived in the great forest which occupies the northern part of the (then) People's Republic of the Congo and the extreme south of the Central African Republic. Almost nothing was known about them. The capital of the CAR is in the south of the country, so it was quite feasible to go there (by aeroplane of course) and simply move southwards into the forest of the Lower Lobaye.

I also had a vasectomy - just in case I might pollute a population. In fact, I 'had sex' only once - with a very charming, beautiful and bubbly hotel chambermaid in Bangui - which was, ironically, my last heterosexual experience. Flights to Bangui (the capital of the Central African Republic located in the south-east of the country on the Ubangi river, a tributary of the Congo) went from Paris, and Paris had the nearest embassy of the CAR, from which I had to procure a tourist visa. I don't remember any part of the journey until I was in the UTA (Union de Transports Aériens) plane bound for N'Djamena (Chad), Bangui and Brazzaville. I remember the excellence of the meal onboard, but not the meal. I remember leaving the airport at Bangui and finding a taxi, whose charming driver took me to his very pleasant little mud-brick home for the night instead of a hotel, and charged very little. Next morning he took me to the city centre, where I booked into the cleanest of the least touristic hotels. Having always wanted to have a very dark skin, I found myself in a rather warm version of my personal heaven, surrounded by beautiful people, especially the women with their wonderful dress-sense, poise and humour. Like most former-French colonies, the Central African Republic had become a military dictatorship - under the rule of Jean-Bedel Bokassa, who, notoriously, crowned himself Emperor in 1977, and bribed the President of France with diamonds a little later. I had been told that I would require permission to go beyond 5 kilometres from Bangui, where there was a police or army checkpoint, so I walked the kilometre from the hotel to the Ministry of the Interior building, trying to acclimatise myself to the heat. I went two or three times hoping to get a piece of paper. On one occasion I remember watching a secretary behind a counter slowly dismantle a telephone in front of her. Maybe it didn't work, but it certainly didn't work after she had pulled it to bits. After a few days (presumably waiting for a piece of paper, a laissez-passer) I was told by a Lebanese who had befriended me that really I didn't need permission and I could just go wherever I wanted. The Lebanese are (or were) a trading class in francophone Africa, importing consumer-goods and retailing them in shops which stocked anything and everything saleable. This young man was amazed to learn that I wanted to go to the forest and find Pygmies. He was also very well informed and expressed his amazement at the situation in Northern Ireland - at how different religious sects could be at each other's throats. This was just 5 years before Lebanon disintegrated in sectarian strife. I took a taxi to Km 5, with my little rucksack, and there I started to hitch-hike towards M'baïki, the nearest accessible small town close to the forest. The police (or were they army ?) being, like most Africans, anxious to be of service to Whites, simply ordered the next driver to arrive at the checkpoint to take me to M'baïki. So far, so good. I got to the little town very quickly, and, being a white man, I was offered a free room at the government guest-house, which effectively separated me from the inhabitants of the town. I remember nothing of M'baïki, except that it was clean and neat, largely mud-brick with tin rooves, just like the outskirts of Bangui which, I had been surprised to see, was not a series of depressing and disease-ridden shanty-towns. Next morning, I started walking towards the river Lobaye and the forest. I remember very little of the short journey to the Lobaye river, except that at some stage I was picked up in a Land Rover by a White Father and brought to lunch at the mission station which turned out to be a large coffee-plantation run by missionaries who lived luxuriously, with plenty of provisions - including pastis - flown in from France. At the Lobaye river, there were clouds of beautiful butterflies, and a ferry operated by a man with a pole. Now the ferry is motorised, as you can see in this photo. It looks very like the old ones they used to have on the river Seine, between le Havre and Rouen..

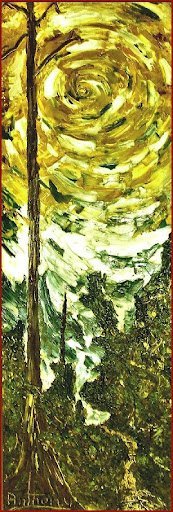

I walked slowly along a shady red dirt road, and by mid-afternoon I had arrived at a small village on the edge of the (more-or-less) virgin forest. The landscape up to that point had been plantations and secondary forest, pleasant, if not particularly impressive. The Chef du village was, of course, alerted immediately to my arrival, and again I was shepherded to a house on stilts, reserved for white visitors. Walking through the little village people were of course curious, and also very friendly - anxious to feed me, if I bought the ingredients. I ended up with a stew composed largely of chicken neck and feet with the usual green leaves to generate some taste, because, being a white man and 'fair game', the cooks quite rightly spirited away the best parts of the scrawny fowl for a feast of their own. I also had boiled manioc (bitter cassava) for the first time. This is a rather tasteless doughy carbohydrate, a staple root-crop, about which you can read here. When there is only an outdoor fire of three small logs to cook it on, and few cooking implements, it can only be boiled, fried or roasted. I never had it fried, but it was rather good roasted. (Many years later I found this to be true also of Bacalhau (salt cod) in Portugal.) That first night in the village (whose name I think was Bagandou), pleasantly relaxed by delicious palm-beer, I heard the Pygmies singing their distinctive polyphonic songs not so far away in the non-virgin forest. This was very exciting, so next day, despite entreaties not to risk my life in the dangerous forest, I left my privileged accommodation and set out on the path into it.

My little rucksack contained very little - anti-malaria pills, tetracycline, a couple of bandages, a battered old Agfa camera and just one film (I have always been quixotic), soft moccasins that I made in Ireland before I left, a couple of maps of the forest (mostly green with contour-lines, but, importantly, with rivers and streams marked) and a blanket. I should have brought two blankets, or a sleeping-bag, because the temperature in the rain forest drops quite considerably at night. I shivered that first night in the forest, as the monkeys called back and forth. I must have brought some food with me from the village, probably papayas (which I had never eaten before and found quite delicious). I also had a small amount of money in the local currency (CFA francs, formerly francs des Colonies françaises d'Afrique but now called francs de la Communauté financière africaine), and some French francs. I probably had some ointment, and I must have had a few good knives.

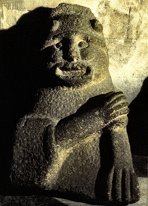

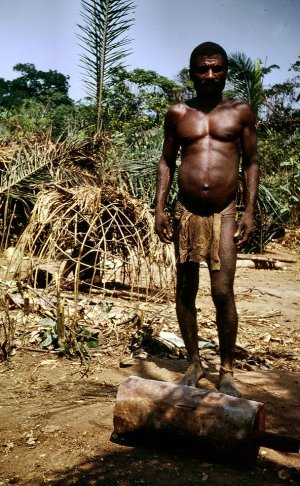

On my second day in the forest a group of Pygmies found me, and were highly amused by what they saw. I was quite intrigued by what I saw, because here at last were real, live Pygmies, many with the distinctive characteristics of 'square' head, stocky bodies, and beautiful feet. The men had flat-top haircuts, and some of them had their teeth filed to points, which is a feature of all Pygmy groups. Another feature of Pygmy groups is that they do not have their own language, but use the nearest and most convenient. This could be because their original language, like that of the Amazonian Pirahã, did not feature recursion (sentences containing independent phrases or sub-clauses). In this part of Africa, the language of trade is Lingala, a beautifully-easy language to learn immersively, and these Pygmies understood my attempts to speak it - learned from a book produced for American diplomats and spies. (I had this book in my rucksack, too.) I don't know whether or not they also spoke the quite different Sango language spoken throughout the Central African Republic. They brought me to their camp.

So - why did it not work out ? They were lovely people and charmingly accepting of the strange thin, floppy white man with glasses who offered them no skills worth having, and could not explain why he was there. I have felt out-of-place in most places for most of my life. When I didn't feel it at the time, I realised afterwards that I was. A person who feels out-of-place all the time, or out of his/her depth, cannot be a tourist. And I very quickly felt that I was just being a tired tourist in the African rain-forest. Maybe I was simply too self-conscious, too embarrassed by my own incapacities. How could a European misfit possibly blend with these happy, singing people ? I ate their food, took lessons on the molorou (the local name for the 'African lyre') and the sanzi (thumb-piano, lamellophone, also known in Europe as the Mbira), started to pick up words here and there to express myself. But my self was not a Pygmy self. I was a typically fucked-up European - what was I doing here ? Was I pursuing a mere romantic fantasy ? Was I patronising them ?

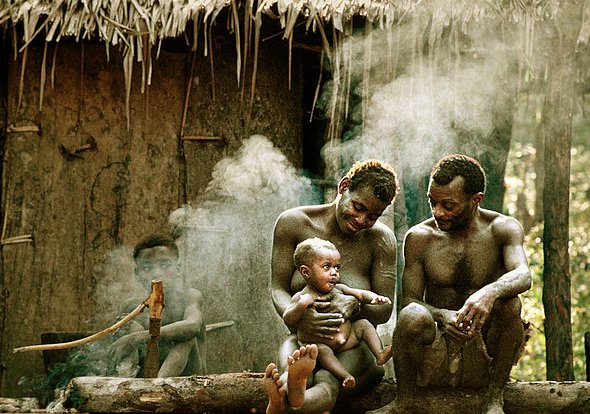

And so I left the rain forest and went back to M'baïki like a good (if quixotic) tourist. And back to Bangui. But how was I to get back to Europe. I still had the outward air-ticket at the bottom of my rucksack. It was one of those tickets with counterfoils and was, to say the least, somewhat stressed: smudged and torn. In a hotel room I managed to change the 'open' (unreserved) destination Brazzaville to a smudged Paris. Next morning I went to the Air Afrique office in Bangui and handed them the ticket. The counter assistant laughed at it, remarking that I must have been swimming with it in my pocket. I told him I had been to the forest. That was all that was needed. He simply made me out a new ticket, destination Paris, and booked me on the next flight out, which was the next day. I had no more CFA francs, but I had some French ones. And so I got back to Paris, at the end of January with almost no clothes, and incredibly inadequate footwear. On the plane I had managed to adapt a rather beautiful real wool Air Afrique blanket into a poncho, which I donned before leaving the aircraft - and which probably saved me from getting pneumonia. I was surrounded by the cold grey people of Europe and their frightening property-insanity, their pathetic and aggressive cargo-cult. I remember trying to busk to get some money, but within minutes a plain-clothes policeman came along and shooed me away. How I got back to Ireland I simply don't remember. I seem to have blanked it out. And in the 40 intervening years of intermittent fatigue I have hardly thought about my failure to become a real human being. But I have seen documentaries on television about the B'aka of the border area covering parts of the Central African Republic, Cameroun and the (Brazzaville) Republic of Congo, of whom the Binga are certainly an offshoot. And since I answered the call by a BBC programme to recount my little travel-scam, I have learned that there are now guided tours for the rich from Bangui to beyond the Lobaye river. I am surprised that the forest is still there, because I saw logging going on in 1973 (or was it 1972 ?) And, moreover, the Pygmies are still there, living their lives only slightly differently from when I was there. They seem to have abandoned the breech-clout. Naturally they have geared themselves for the tourists, and probably are gradually losing their close relationship with the forest. This is a photo taken by a tourist who not only had a decent camera, but could use it. But these Pygmies are at the edge of the forest, and there are hundreds - if not thousands - of square kilometres of forest to the south, east and west, where almost nobody goes - except the self-styled conservationists...

read about my mini-brush with the BBC, which led to this page being written >

PSEUDO-ECO COLONIALISM - THE LATEST THREAT World Wildlife Fund heavily and violently involved in Conservation scam in partnership with EU, logging companies and other transnational bullies.

|