LAST CHAPTER

a curious and peculiar kind of queer,

part

eighteen of

ONE NOT ONE

|

In Amsterdam I sat 'stoned' in the vast 19th century neo-Venetian main post office, having just stolen teddy-bear postcards from a booth. During the week I was there I went to only one museum - the custom-built, brutalist monstrosity which is the van Gogh museum and a desecration. It almost destroys the paintings within, which were painted to adorn the houses of ordinary people. It is a temple to vainglory and money, and everything that Vincent was not and could not relate to. I was so appalled by my experience there that I did not go to any other museum or collection in the stodgy, tourist-ridden, stifling city of pleasure that (like Paris) is not good to be alone in. I had expected to love my week in Amsterdam, because I had been there some 25 years earlier with my Danish girlfriend, and (probably because of her and the friends who were with us) thought it delightful. As for paintings, I had slides of all Rembrandt's self-portraits and most of Vermeer's work at home - a far better way of studying most Old Masters than going into the hostile environment of a gallery. I was glad to take a non-luxury bus across the flat wastes of the Netherlands and Northern Germany to West-Berlin, a city-state I expected to dislike, but was surprised to find that I loved. Neither Amsterdam nor Paris have half-decent parks, but London and Berlin have huge ones which are like lungs. I had been invited to attend the opening of my little show of Metamorphotos at a café-bar in Schöneberg called Anderes Ufer, managed by the very sweet, kind and generous Reinhard von der Marwitz, who put on exhibitions for no gain or profit, taking no commission from the infrequent sales. Vincent would have been happy to show here, even though Vom anderem Ufer (On the Other Bank) is a polite term for Queer in German. Looking it up now in Google, I find that ten years earlier David Bowie had frequented and supported it. Nobody told me at the time - not that I would have been particularly impressed. Michel Foucault was also a patron.

Some of my metamorphotos were later repreduced in Babilonia, a magazine published in Bologna..

He had arranged for me to occupy the beautiful flat of a friend who was holidaying in Brazil, a spacious, bright and airy apartment with a balcony overlooking the Winterfeldplatz, which had a market on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

Because I had not expected to spend more than a weekend in Berlin I had not taken any trouble to learn any German before leaving Ireland. Because Karl-Heinz came from East Germany and was a bricklayer by trade, he spoke no English. He had been gaoled as a Political Undesirable homosexual of no use to the Stasi, and was bought (freigekauft) by the West German authorities for the usual handsome financial consideration. He spoke a very clear German, he used his hands expressively, and took the trouble to define and explain words that I did not know. My knowledge of Danish gave me a large potential vocabulary, and I did not find the German verbs difficult. So we managed to communicate by speech as well as by touch and, especially, with our eyes. He was a good teacher, so during the four days of cuddles, wrestlings and joy that we shared I learned quite a lot of the language - enough to have brief conversations with other Germans, buy food, and so on. He was the first - perhaps the only - man I have ever felt completely at ease with, one of only three that I have wanted to live with or close to.

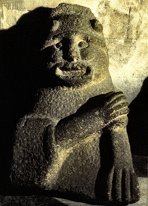

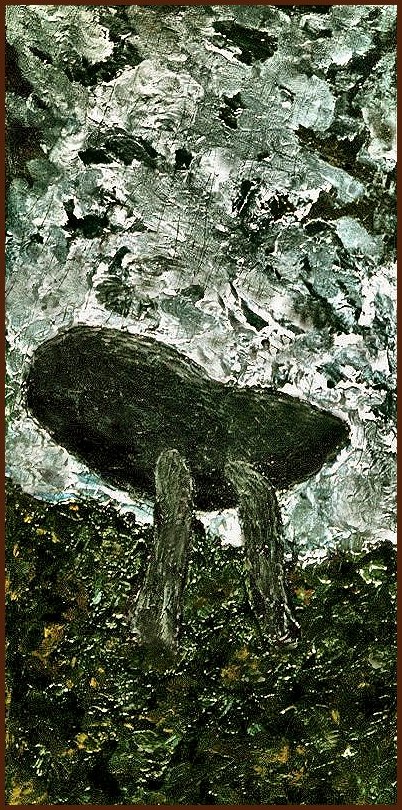

Bigfoot

: portrait of Karl-Heinz in the Winterfeldtplatz flat.

A week was not long enough in West Berlin. I did not have the money to change my plans, and so I returned, via bus and aeroplane to overpopulated London, and on to Ireland. At Schiphol airport, hares crossed the runway between planes taking off. How wonderful that they could adapt so well! We have a lot to learn from homeless hares. On the long bus-ride to Berlin I had one of my delicious picnics, often enjoyed on cross-channel ferries, trains to Paris, and (for many years) on trips with my mother to Irish Megaliths and to Romanesque churches in France, Spain and Portugal. Our picnics were composed of the simple best of what was available in bread, cheese, salads and fruit. My mother would have loved the delicious German Bauernbrot (so much better than the frumpy pain de campagne of France) of which I ate a great deal when in Berlin. Often eaten beside a megalithic tomb or stone circle, or in a graveyard beneath bizarre and amusing corbels (some of them exhibitionist) depicting sins which would lead to eternal damnation - which was often depicted on doorway capitals.

After one picnic near Poitiers I was so sleepy (though we never drank wine in the middle of the day) that I looked the wrong way while driving across a dual carriageway, and our little Renault 4 was hit and wrecked by a fast, oncoming car. We sustained no injuries, however, and my mother reacted magnificently. After the initial shock and onset of bleakness she said: "Well, shall we hire a car and continue the trip ?" The trip was the first I had planned and mapped out to investigate the origin, purpose and distribution of exhibitionist churches on Romanesque churches, and their subsequent metamorphosis into the crude "sheela-na-gigs" of the British Isles. So we got a lift into Poitiers, hired a car, transferred the contents of the Renault 4 (sitting behind a garage conveniently situated where the accident had occurred), and proceeded on our scheduled journey. The car had not been comprehensively insured, so, although it was ferried back to Ireland free of charge under her travel insurance, my mother received not a penny for a new one - nor even the scrap value. But she showed no anger or dismay. She was simply thankful to be alive and unscathed. We had many more delightful picnics and trips in France, Spain and Portugal (mostly at her expense, but still cheaper than the winter holidays she took alone in Cyprus; unlikeme, she never did things 'on the cheap' and never bought things either second-hand or by deferred payment/hire-purchase) but we never again brought her car across the sea - and we never caused a biteen of damage to a hired one. Twenty years later, however, when I had given up motorbikes (by then no longer cheap forms of transport but mechanised posing-pouches for yuppies) and had bought a car (second-hand like almost everything else I have ever bought), I started taking ferries to France again, visiting megaliths and churches not with my mother, but with Malcolm, my non-sexual and cuddly soul-mate, who so loved the country that he joins me here for a large part of the year. Unemployable like myself, he lives on (many would say "scrounges") a government hand-out... Trips with Malcolm also included visits to men I had communicated with by mail (and, later, by e-mail), and the occasional 'gay' bar. But by the time we were making trips to France together - even though our relationship was as platonic as a relationship between two manloving men can get - we had given up seeking sensual adventure and were largely indulging in a little socio-psycho-sexual observation and trips down memory lane. Malcolm was never adventurous, in any case, and almost asexual. So even when we tried 'threesomes' he was more or less an 'add-on' to my adventure. On one trip to Paris I re-acquainted myself with a very beautiful, sweet and shy Camerounian called Victor, who may have been a relative of a Camerounian intellectual, writer and film-director born in Bangui (Central African Republic), the only sub-Saharan city I had ever visited (on my way to the Lobaye forest) - and which, under Emperor Bokassa, was not a city of shanty-towns, appalling misery or violence. Victor was not only very shy, but was deeply ashamed of his poverty, and refused to allow me to visit his (probably shared) accommodation in the 20th arrondissement. My borrowed "Paris Pad" was not exactly luxurious or even clean, and its toilet was on the landing outside, but it was quiet, and perhaps Victor's was noisy, rat-infested and a health-risk - though I doubt it. But one never knows... As I have said earlier, I have always been deeply attracted to black skin (the blacker the better), and to African hair, especially when the bearer-wearer has a classic round Hamitic head. But my encounters with men of dark colour have been sadly few, and simply sad. A gorgeous and rich Sudanese employee of his country's embassy in London took a shine to me (in the famous subterranean Men's Convenience on the Charing Cross Road close to the National Gallery), and used to take me for a delicious vegetarian dinner to the long-established Greek restaurant on Queensway, which was much too expensive for me. I would then take the sweet and sexy man back to where I was staying, close by - and inevitably he would ejaculate within two seconds of opening his trousers. I could have wept- not least because he hadn't taken off his shirt and tie to reveal his beautiful torso. I wasn't so much disappointment as sad for him and his disappointment, because I could have given him a lot of pleasure - thanks to the shiatsu I had recently and informally been inducted in by a very sensual 'New-Ager' from Dublin who visited me several times in the county Down. I could have had Umm Kholthoum singing in the background - or a vinyl disc of Brahms' first string sextet which I had recently bought at the Record Exchange, Notting Hill Gate. Much the same thing happened in the love-meetings between Victor and me, though at a slightly later stage. I usually give people love-names, and I called him Monsieur le Missionaire, while he gigglingly called me Monseigneur Cannibal. I certainly could have nourished myself spiritually by licking him from head to toe. With Malcolm, we had delightful walks through the cités and passages of central Paris, ending at the Palais-Royal, where I took this photo of a splendid 'water-feature'.

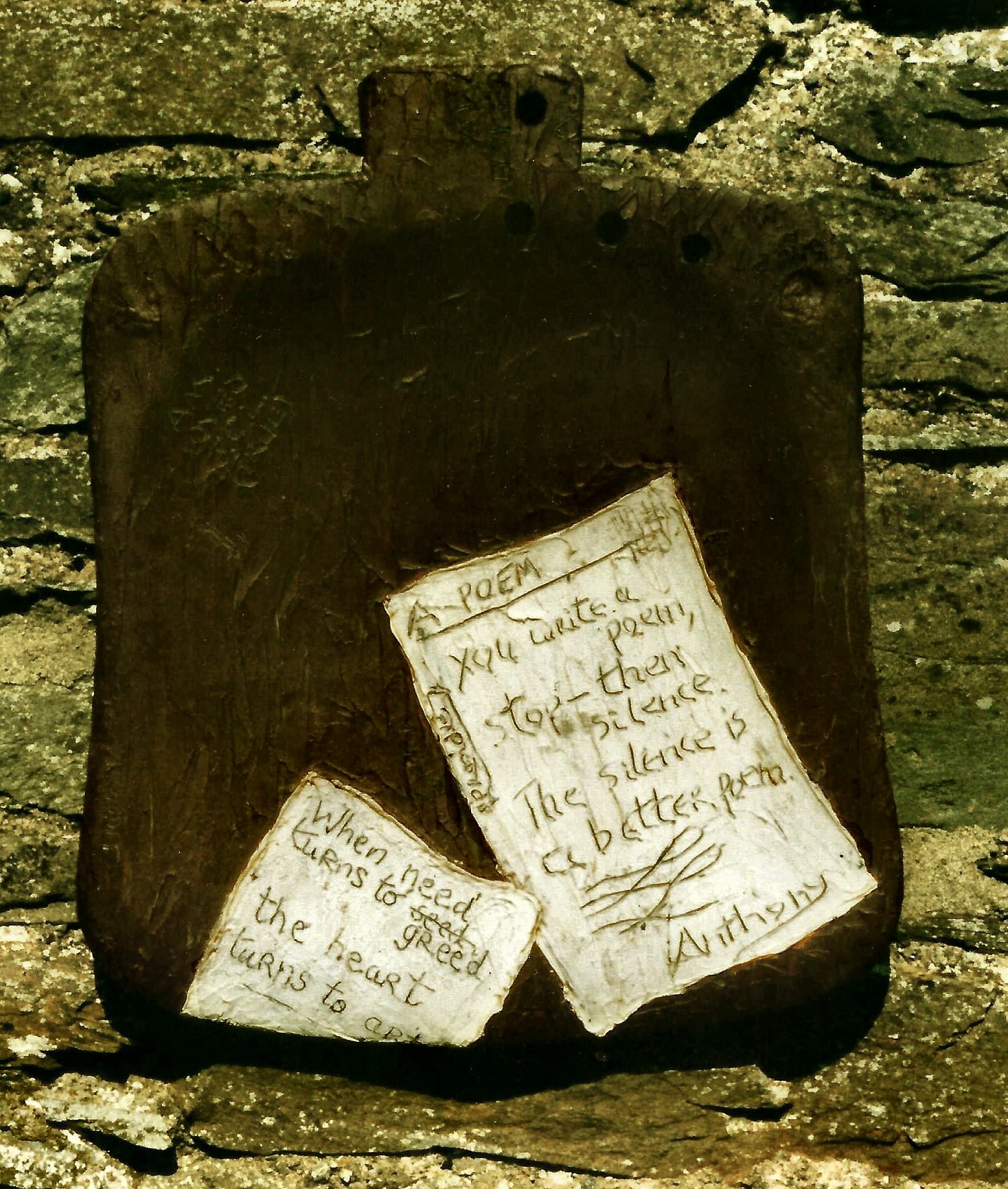

Thus my encounters with people of a much more beautiful 'race' than I have been unsuccessful. But the 'next best thing' are bearded and hairy men of my own pinkish-grey complexion. I dare not imagine what cuddles with a bearded and hairy 'Binga' could be like... 'Words are a plausible army...' I have been writing poems on and off since I was sixteen, when my very first poem, in French, actually made it into the school magazine. Sixty years later, I still think it pretty good, though owing a lot to Paul Verlaine, that old goat of a poet who would have had sex with anything that moved, clean or unclean, anal, genital or buccal, male or female. I have written other poems since, in French, and Albanian, but mostly in English. A poem I wrote to the Commanding Officer of the RAF Intake camp I was disappointed in, may well have got me out of the RAF cleanly and efficiently. It was one of the many not-very-good Shakespearean sonnets I wrote in my twenties, which included the line Wings on a man do not make him a bird. Translation of poems from other languages taught me to write good poetry. But, having no ambition, I have only half-heartedly sought publication - and my best collections were self-published (by Dissident Editions) just for the fun of designing them, visiting printers and binders and getting myself ISBN numbers. I buried most of them in my county Down badger-sanctuary and elder-tree thicket, which I bought as an eventual burial-place but will probably not use, since I will most likely die in France. My grave is already rented and reserved for 30 years, and is in a beautiful spot overlooking the river Aveyron at Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val, some 12 kilometres from where I live. (Not that I will be appreciating its leafiness, not that anyone will visit it.) I have just remembered another - very brief - encounter with a handsome (but - I guess justifiably - touchy - and, alas! not touchy-feely) American called Linwood: I

met a lovely dark-skinned guy - But no joyful cry.

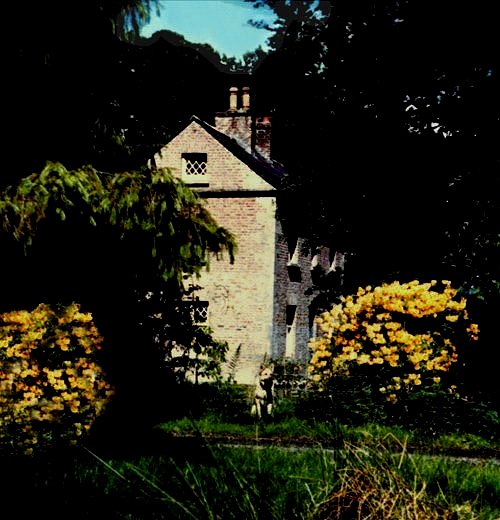

I had no wish to find another 'girl-friend'. I was still infatuated. I can't remember how I passed my days, but this was almost certainly when I discovered furtive men showing their cocks in urinals, in between my small shoplifting raids on the only two bookshops in the centre of Belfast. This would also have been the time when I stole oil paints in a shop which also sold big expensive reproductions, including prints of paintings by van Gogh. One of the books I stole was of the great, vincible Vincent's letters. I almost became infatuated with him. The Best Friend (an Alan) who replaced me in Copenhagen had introduced me to a friend of his who was Homosexual. He was a very nice, hospitable guy and I remember thinking that it was amazing that men had loving, sexual relations with other men. But I never asked him anything about himself; I was too wrapped up in my dizzy infatuation. I never went to see him after my return to Belfast. It would have been around this time, too, that I read Peter Wildeblood's famous Penguin book Against the Law – a powerful call to decriminalise 'homosexual relations' that eventually led to the British law being changed in 1967. It remained in force in both parts of Ireland, however, until the 1980s. After a few months of my aimless hanging around, my mother finally browbeat me into joining the RAF. I was a star recruit to train as a translator - but by this time (nearly ten years after the Suez Crisis/Anglo-French-Israeli aggression) I had turned anti-British. I had hoped to learn Arabic and help the South Yemenis in the Aden Protectorate drive out the imperialists. This, of course, did not happen, because I was expelled from the RAF (on pychological grounds) within the month, to the chagrin of my mother and aunt. If my father had been a dead pilot he would have been revolving in his watery or sandy grave. But perhaps he had not been a pilot and was still alive. In fact, he had been a pilot and he was still alive. The only thing I could do was return to university. At this time university was free for all, and many students, including myself, qualified for living allowances. It was with the first three months' living allowance of my third year that I had skedaddled to Denmark. Now, amazingly, I could return with the same living allowance bestowed on me by the Education Authority. But I realised that I could not keep on living at home. So – it was as simple as this in the mid nineteen-sixties – I went to the little office of the National Trust for Northern Ireland, then largely a one-man affair run by a very kind Anglo-Irishman with a double-barrelled name, who also was trying to create an Opera company in Belfast. Perhaps because I 'spoke nicely' he offered me one of two vacant properties: a Georgian gate-lodge at Castle Coole in county Fermanagh, nearly 100 miles away,

So my mother took me and a few redundant items of furniture, fabrics and kitchenware from my childhood home and established myself in this wonderful first-time-residence in leafy and protected rurality only 3 or 4 miles (as the crow flies) from the Queen's University of Belfast, where I resumed my course in Philosophy. I begged and stole other bits and pieces, including a Bang & Olufsen battery-radio so that I could listen to classical music from the BBC. In those days it was amazingly easy to steal from high-end, high-profit shops selling records and sound equipment, In none of my future homes would I have a television set, and only recently did I acquire (a gift from my neighbour) a washing-machine. Thus continued a life of relative isolation from the culture and mores around me. It was there that my interest in plants was born. The quarter-acre had a handsome laburnum tree, a forsythia, a bed of Japanese anemones, and not much else that I remember. There was a sprawling and impressive Cotoneaster integrifolius (which I did not identify for decades) at the southern gable, where a blackbird had its nest. So I decided to put plants against the bare brick walls of the house. I knew nothing whatever about plants, so I sent for a catalogue from the well-known Daisy Hill Nurseries at Newry, county Down...and chose, amongst others, Ceratostigma wilmottianum and Teucrium fruticosum. Here at Caylus I have (as well as Japanese anemones and a Cotoneaster integrifolius) both these plants, my faithful wards since 1966. I kept in contact with Daisy Hill Nurseries until they finally closed in 1996, buying many plants over the years from Paddy Hanratty and the lovely, generous Peter McCann ('the only man who could make a walking-stick take root') for my various gardens. Through them I also had a plant-swap arrangement with the Irish National Botanic Garden at Glasnevin in Dublin. Of course, I generally prefer plants to people, and possibly to dogs. At Ballynahatty I had nothing to put on the inside walls, either. Good-quality reproductions of good paintings were rare, expensive, and very difficult to steal – although I once managed to secrete a Vlaminck village-in-snow-and-mud underneath a raincoat from the Magee gallery and art-materials shop in Belfast. From there I also stole paints and a palette-knife, and, on the full-size ping-pong table in the adjoining empty half of the semi-detached cottage, started to paint on the back of thick wallpaper. This, so far as I can remember, is my first painting : Sun on the Sea, from 1963, crudely inspired by Seurat. It was painted on the islet of Christiansø, Denmark on the back of a strip of wallpaper. I stuck it on to chipboard and hung it up.

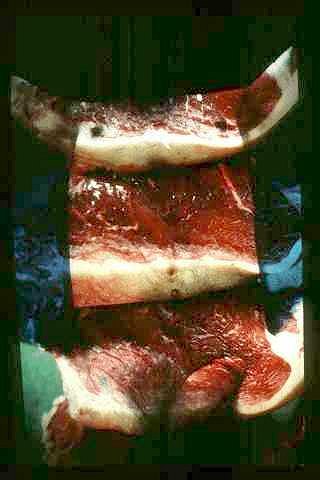

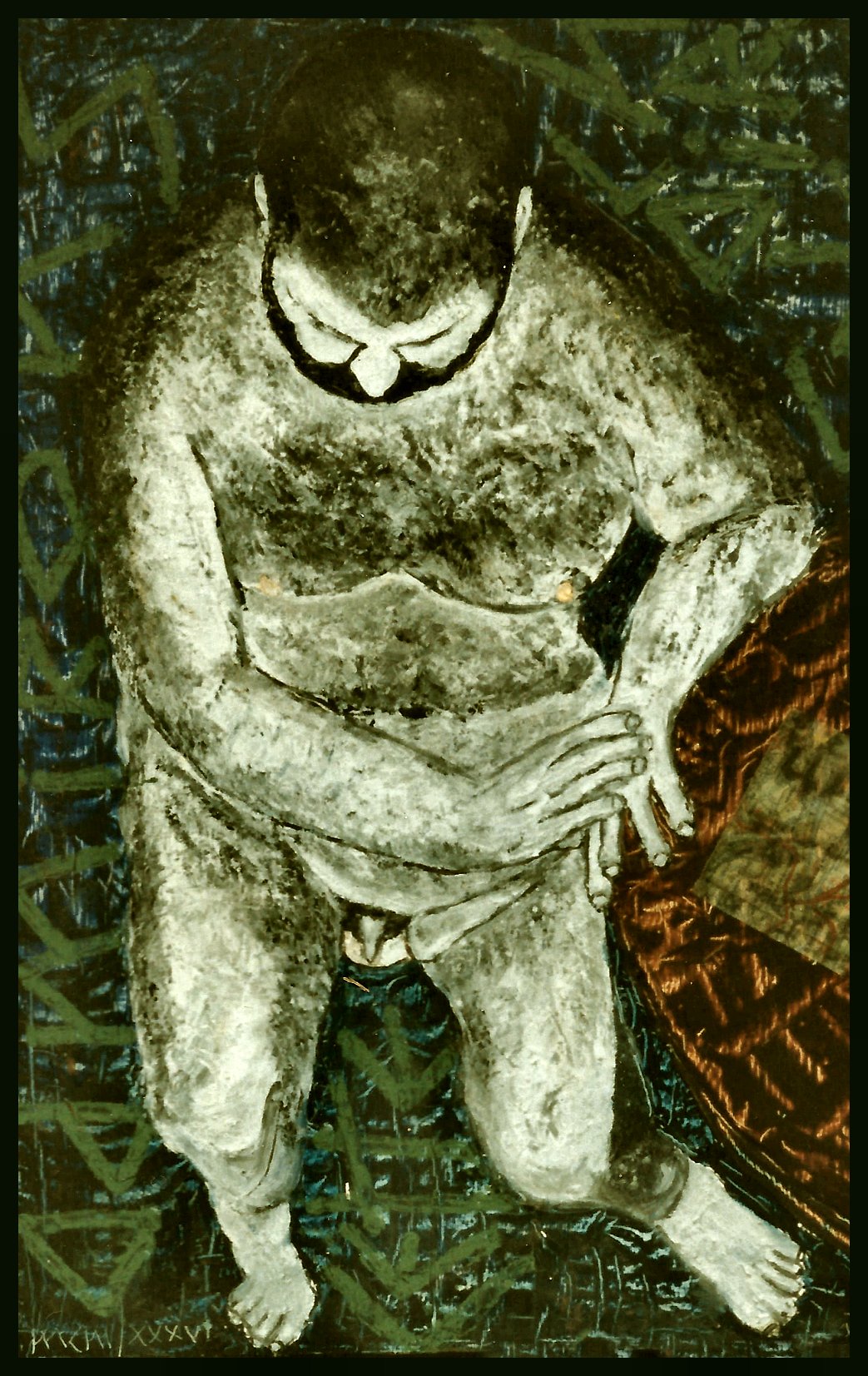

Years later, I made off with the first ever Field Guide to Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland, which directed my energies towards visiting megaliths for forty years. One of those megaliths was just a few fields away in the same townland, Ballynahatty. Much later again I discovered that The Giant's Ring was a cruising area for men with cars, as well as a popular place for walking dogs. Public toilets tended to be meeting-places for men without their own transport, perhaps including the painter Gerard Dillon, of whom I was completely unaware, even though one or two of his paintings was on show in the then Belfast City Museum and Art Gallery, now the Ulster Museum, a place I have always disliked. He was, apparently, a hit-and-run closet-case, and, had we met urinally, I would probably not have learned that he was a well-regarded painter. Maybe we did see each other, but my visits to urinals were unproductive, partly because I found the men who haunted them so physically unattractive (until I went to the 1980 Dalí exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris), and partly because I have never been interested in on-the-spot relief (which I could achieve rather better 'in the comfort of my own home') – but rather in a beautiful erotic rite. Gerard Dillon (whose painting in the link above is obviously a rather strained – even insulting – comment on van Gogh's Potato-Eaters, a Zola-eque masterpiece that I worshipped) had an excellent sense of composition (something more innate than inculcated) but poor technique. At the time I started to paint, I was encouraged by another Belfast painter, Colin Middleton, a very kind and open man who had excellent technique and an impressive range of styles, though I didn't know that (or much about him) at the time; he was a friend of a friend. I guess that he was a superb teacher. If I had had someone like him in the Nissen-hut art-room at Campbell College school for young Presbyterian gentlemen, instead of the totally inept and drawing-focussed Art Mistress, I would not have doodled or played Battleships in excluded boredom at the back of the class, having decided that 'art was not for the likes of me', while Miss Anderson confined her attention to those blessed with neat and tidy Representational Drawing Ability. When I was at University I developed a non-sexual (or unconsciously-sexual) crush on another secondary-school art teacher who, with his high cheekbones and gingery hair, looked like my hero Vincent. When he contracted jaundice, I visited him every day. He loved rock-climbing, so I tried to emulate him. My poor co-ordination, however, ensured my ineptitude. I tended to scramble, use my knees too much. Later, Ivan Firth became part of a mountain rescue team. Had he had overt homosexual tendencies I am sure that I would have become a tiresome acolyte. I painted simply to have pictures on my walls. I have never thought of them as Works. I enjoyed doing them, not really knowing what I was doing, learning the names of colours and squidging paints together with my palette-knife on the ping-pong table next door. I have never been able to paint on an easel, and I have never been able to draw – except (latterly) with paint squeezed in squiggles or arcs from a tube. Thus, completely self-taught, my output might be described as somewhere in between Primitive and Outsider Art – definitely not Naïf. I started off being Representational, but drifted into Abstraction over the years, as I educated myself by means of stolen or remaindered art-books and, eventually, art-galleries in London and Paris. Continuing my curious (perhaps testosteronal) obsession with the iconic image of a bull (I even called my cottage Taurus House) I went on to paint a dying bull as bovine meat. (I wonder what happened it.) It may owe something to Rembrandt's painting of a carcass. Note the crude use of palette-knife.

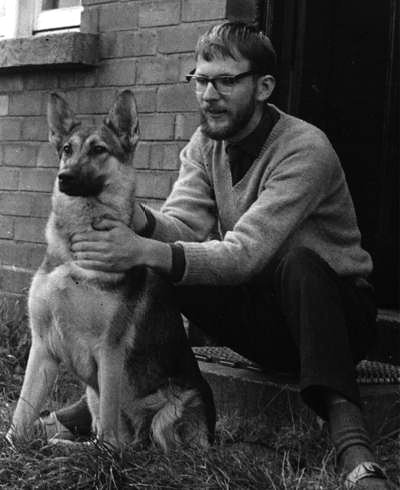

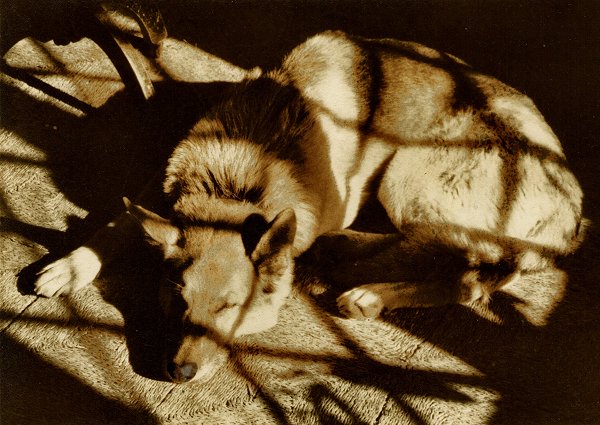

Soon after I established myself, with oil lamps and double-ring gas picnic-stove to augment the coal-burning range, I got myself a dog from the SPCA in downtown Belfast: a beautiful German Shepherd bitch whom I called Elektra. (I had been hugely impressed by the black-and-white Greek film of Euripides' tragedy with my erstwhile truly-beloved in Copenhagen.) The four-footed Elektra became a more worthy object of my brimming love. I had always loved dogs, but had never owned one. She was also the means whereby I re-connected with my long-suffering aunt, and my (still-unconfessed) mother, who was soon to retire from her vice-principalship of the junior school, where her unbeloved freemason father had been principal before the war. She had been born in the principal's house, and she would die a mile away, to be buried just 200 metres from where she was born. Both "my aunts" (as I had always referred to them) took to her, despite their reservations about how competent I would be to look after a dog 'properly'. Dogs tend to connect doggie people, as, indeed, cats connect feline-oriented folk.

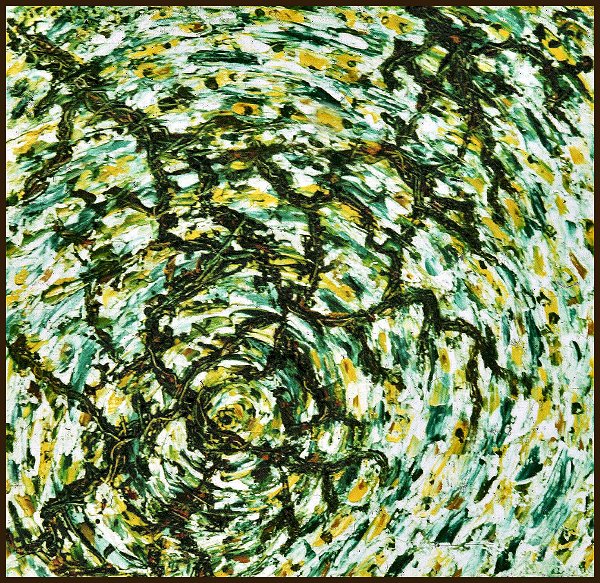

I had been re-enrolled in a philosophy course at University - mainly a means of acquiring a living-allowance. I had quickly learned that philosophy had little or nothing to do with wisdom, and, although I loved Aristotelian Logic and admired Socrates and Thomas Hobbes, I was pretty disillusioned. I attended as few tutorials as possible. I devoted my life to Elektra with a sideline of painting. I was supposed to be devoting my brain to the study of Schopenhauer. The river Lagan was not far away, and Elektra loved swimming, so many afternoons were spent on the towpaths throwing sticks into the water. I painted Elektra swimming – another lost picture. Eventually, my professor, a very wise and lovely man who also lived in a National Trust property some 30 miles away, told me to attend just once a week: his 2-hour Friday seminars on Æsthetics. These were wise delights, going inspiringly into one ear, and out the other. They pre-dated John Berger's very male-heterosexual Ways of Seeing. All other pictures from this period are lost, but I have a photo of the next phase in my 'artistic development, obviously inspired by the Great Vincent: sun and dead tree (a premonition of global warming ?)

I was still struggling to use the palette-knife with my clumsy, stubby fingers. When

I was sixteen I wrote a poem

in French about the self being a leaf My ever kind and imposed-upon aunt Marcella had stumped up the money for me to buy a second-hand Lambretta scooter, which was not the most reliable means of transport, but often got me to the university in ten or fifteen minutes. I hated leaving Elektra alone as much as she hated being left alone. She was a resourceful dog and worked out how to turn round door-knobs with her teeth, so one day she actually appeared, panting, at a Friday seminar. I have no recollection of how we both got home. She would not sit on the running-board of the scooter, so I must have ridden back home at walking-pace. Of course, in the end, I was not awarded a degree because I devoted nine papers to writing an adolescent rant against the aridity of Western philosophy. I had read very little Schopenhauer, and what I had struggled through I didn't remember. I never remember more than the drift of what I read. I could tell you almost nothing about the great novels that greatly influenced me, not even the names of the chief characters. I can read a book or watch a film twice or even three times as if it were the first. I had thought of simply not turning up to sit my Finals. I guess I was echoing the famous Paris Events about which I knew nothing in a kind of nihilistic Nietzschean post-Existentialism. Bryce Gallie, my sweet professor, actually came to my house actually wringing his hands to tell me that I hadn't received a degree. I had to calm him down and offer him tea. I couldn't have cared less [or, as Americans say quite wrongly, I could have cared less]. I had no map of my future, I was reasonably content to drift from day to day with my lovely dog. What could one do with a degree in philosophy from a second-rate university ? Only teach philosophy or get a graduate's job in an office. I regarded my 'failure' as my only badge of honour in my resistance to the Lumpenbourgeoisie. Over fifty years later I am still (slightly) proud of my non-achievement. So I never became the doctor that was expected of me when I was a boy. I would have made a terrible doctor, even if I had had the requisite competence in memory, mathematics, physics and chemistry. I was very keen and good at biology at school, but that was not enough. I would have made an even worse dentist, with my stumpy hands and spathulate thumbs. Apart from those considerations, my allergy to hierarchy barred me from most employment. That allergy was injected into me by Campbell College, on leaving which I vowed never to submit again to rules I did not understand or did not endorse. However, I had been approached (through an anarcho-nihilist l PhD-student friend in the philosophy department) by a desperate Belfast College of Technology (housed in a hideous Raj-infected Victorian building partly-masking the elegant Georgian frontage of the Royal Belfast Academical Institution) to 'teach' classes of Day-Release students / victims what was delightfully known as Liberal Studies. I was offered payment as a subtitute teacher to take charge of twenty or thirty men at least as old as I (and much more savvy) and tell them about the British Constitution or the Parliamentary System, the Freedom of the Press, The Cold War or other improving knowledge. There was, of course, no syllabus. These guys (no dolls, and all Protestant) considered the class a break from a whole gruelling day of technical lectures on electrical or aeronautical engineering. They were quite right, and I told them so. Inspired by Professor Bryce Gallie, I said that we could discuss anything they liked, or they could leaf through the gutter-press and soft-porn magazines, or design very sophisticated paper darts. (Most of them were from the Shorts aircraft factory.) It was a jovial conspiracy born out of a ridiculous situation, and I had no problems. We all knew the situation, and nobody lost out. I had been in a similar farcical situation in Tunisia, where I had been a lecteur d'anglais in 1960 without any instruction whatever, neither on how I was supposed to provide English Conversation via my rickety French to 30+ North African Arab teenagers, nor on the required or expected subjects of discussion. The British Embassy had not even seen fit to tell me (nor the three other lecteurs d'anglais) that payment under the French-designed system would not be made before the first three months had been pennilessly endured. Shoplifting is impossible for a European in North Africa, though I did manage to purloin a fancy volume of Villon's poems from a European bookshop in Sousse, where I had been placed. This was (I discovered much later) where André Gide had had assignations on the beach, and I once had the moonlit privilege of sucking the dusky cock of a nice old line-fisherman who spoke only in Tunisian Arabic and grunts of pleasure. On a weekend visit to two other lecteurs living in Halls of Residence in Tunis, I stupidly stole sheets and a bedside mat to make my flat more comfortable...and was as a consequence fired from my 'position'. My friends/colleagues were, of course, appalled. I had to leave. Without any money to pay for my passage, I persuaded a freighter captain to take me from Sousse to Manchester in return for work on board. After two hours in the engine room I was sick...for two days. I was not encouraged to return below decks, and was exquisitely bored for at least two more until the boat entered the Manchester Ship Canal. In the end, Mattie had to send a cheque to the captain to pay for my voyage. My misdemeanours were mounting up. This one was probably also the biggest mistake of my life by altering its course entirely. Had I stayed the full academic year in Tunisia I almost certainly would not have gone to Denmark in the summer, and the unfortunate results of my eventual calf-love affair with a very damaged young woman would never have occurred. I had closed off almost all options, and all the hopes of Mattie and Girlie. By 1967, I was painting more life-like bulls.

Though I was being paid small sums (in arrears) by the Belfast Education Authority on a casual basis, I was still without a student-subsistence grant from Belfast Education Authority, so I had to resume my shoplifting of foodstuffs, books and clothing. A few years later (after my abortive attempt to go and live with 'Pygmies') I would spend three months in Belfast's now-historic gaol for shoplifting food. I had become a kleptomaniac. But before that I would lose the lovely Elektra to an electrocution machine because she had started to chase nearby sheep, due to my failure to monitor her movements. This brought on an episode of weeping misery so great that I signed myself in to a psychiatric unit – then signed myself out again. Far more terrible to lose a beautiful and sweet dog than to be dispatched without a degree from the Queen's University of Belfast. I buried her in a corner of the garden of my erstwhile home in Belfast, marked by a lovely granite stone, on which I had painted her name in the pseudo-Greek lettering which for some reason I adopted to sign my paintings. The loneliness lasted a couple of (urinal-visiting) years, and then I went again to the Animal Shelter. Another German Shepherd, this time male, and with a given 'name' : Shep. So he remained Shep, even though a 'name' is only a call to a dog, not a nominal designation. He was not as bright or as beautiful as Elektra, but (of course) a sweetie. Unlike human beings, All Dogs Are Fun. As with Elektra and subsequent dogs, we 'bonded' immediately. "My aunts", Mattie and Girlie, also loved him.

I accepted the best offer: of a beautiful house and a part-time job as a gardener on the estate of the Earl of Caledon in county Tyrone. This lasted less than a year, but, having actually been officially employed I was eligible for Unemployment Benefit, and thus, being unemployable in a very (possibly uniquely) liberal-socialist system (unimaginable in the turbo-consumerist-capitalist world of today), my financial future was secured. Shep and I moved house, with the help of a tinker friend of a chap in my Liberal Studies class, and his rather rickety oil-burning low-sided lorry.

This journey to the Head Gardener's house of a Stately Home was, of course, the latest visible evidence of my Descent from the Middle Class to the infernal (but select) circle of the pseudo-intellectual déclassés. I now live on the rue de l'Ifernet, a corruption from Occitanian, meaning 'street of the little hell' because it led down from the old castle to a (presumably fœtid) swamp. In another part of the village is the chemin de Paradis, leading up to more salubrious heights. The Head Gardener's house had a bathroom, four bedrooms, five fireplaces, a living-room, dining-room, kitchen and pantry. I don't remember whether or not I painted any pictures at Caledon, but it was from there that I started visiting prehistoric monuments: tombs, petroglyphs and stone circles. My mother had retired, and her only recreation was golf. So she welcomed the opportunity to take me, Shep and Estyn Evans' Field Guide on jaunts in her car. Thus began the hundreds of trips made all over Ireland to compile my own Field Guide, which is now an elegant and useful website with hundreds of photographs. It is paired with another website on (mainly) Romanesque 'marginal' sculpture and the curious grotesque, crude late-mediæval figures known (unhelpfully) as sheela-na-gigs - mention of which I found in Estyn Evans' guide. Researching these, Mattie and I travelled to France, Spain and Portugal. Shep (who dined mostly on venison and hare provided by the earl) incurred his ire – first by chasing the fallow and red deer through the tulgy woods, and then, when confined to the extensive walled gardens, by treading on some of the Earl's thousands of seedling Christmas Trees. This, plus his dissatisfaction with the crookedness of my vegetable-rows, led to our dismissal – and to my eligibility for Employment Benefit of (so far as I can remember) £3 a week, on which I could easily live.

Shep died from a kidney disease (transmitted, I was told, through rat-piss) just before I moved (in an emotionally-numbed state – no howling grief this time) some sixty miles (in another old, open lorry) to a damp house on the eastern shore of Strangford Lough. It, too, belonged to a member of the aristocracy: the last surviving member of the house of Vane-Temple-Stewart, marquesses of Londonderry and notorious exploiters of the coal-mines of north-east England. The last marquess had entertained luminaries such as Hitler's foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in the 1930s, and his Irish residence some 16 miles ESE of Belfast included famous gardens planted by his mother who gave them to the National Trust. His surviving sister judged me suitable to live in the rather basic stone cottage at Kilnatierney (Cill na Tighernaí in Irish) on the edge of her property, which extended beyond the wall of the demesne. The come-down in quality of dwelling was partly compensated by its closeness to a bus route, which, following the expiry of my scooter, was a good road for hitch-hiking to Belfast. Thus I could visit my "aunts" every week, and it was convenient for them to come to me on Sunday mornings, when we walked along the shore to buy eggs from a neighbour, and I provided lunch. We started drinking wine. It was the 1970s. Here, where winds whistling down from the Mountains of Mourne and across Strangford Lough could be fierce, driving rain into the flag-floored scullery, I took up painting again, on my knees, on the floor. This painting of the shore shows Church Island which is accessible by foot when the tide retreats a kilometre. It had fine mussel beds. The man at the water's edge is not a corpse, but the unfortunate Jim Little, mentioned in chapter two, who fastened on to me (I called him Jimpet the Limpet) and occasionally wanked me off in brief sessions which were loveless on my part. I was not 'flooded with endorphins'; indeed, since my brief time in Denmark, it has been only after the most passionate erotic pastimes (fluidified by weed) that the endorphins have been persuaded to flow. I had met Jim in the public convenience in Newtownards (nearly half-way to Belfast) and used him (like a couple of others) as transport home in his car. It wasn't until the life-changing event in the Centre Pompidou that he left my life – in jealous and miserable rage.

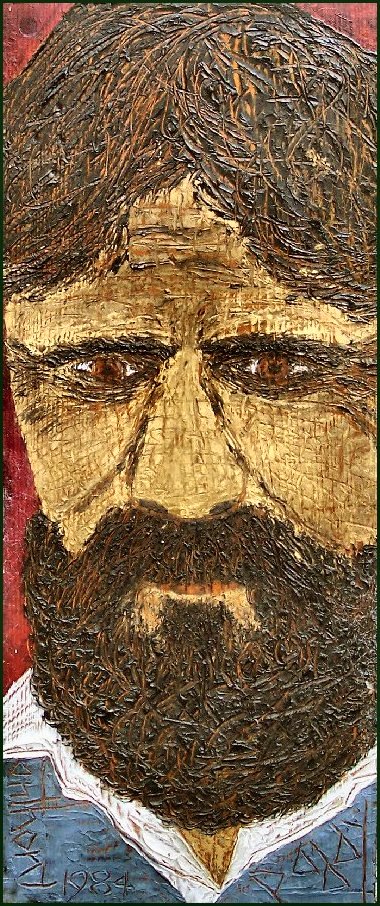

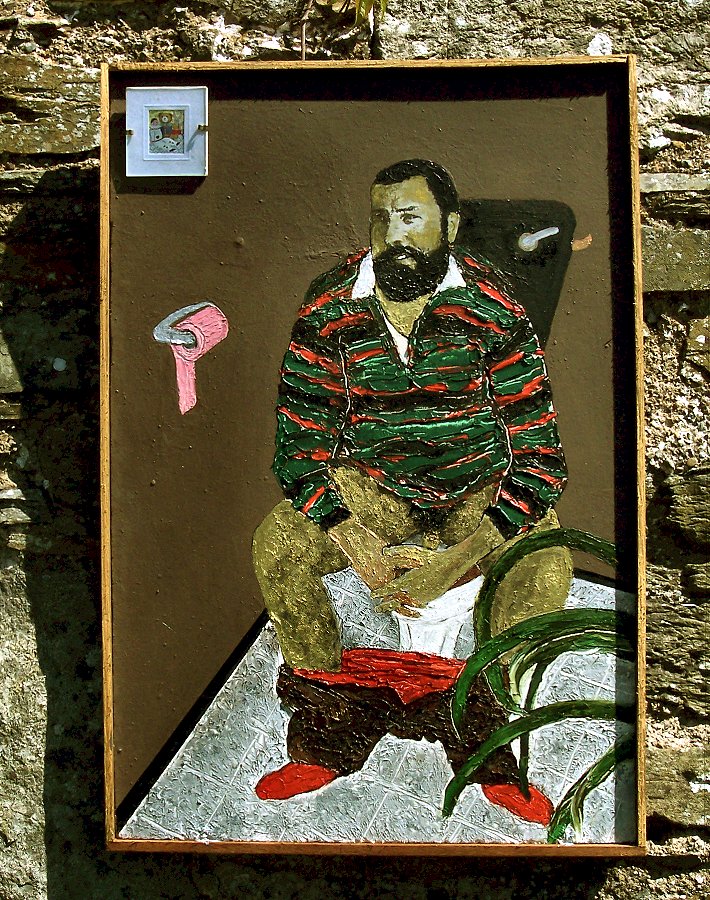

This is my portrait of Patrick Walsh – painted some ten years later, after I had moved house for a third time. By 1984 I was much more adept with the palette-knife, and was hugely enjoying portraiture of bearded friends and lovers.

In Caledon I had become interested in translating poetry, due to seeing many terrible renditions of fine poems into painful 'translatorese'. Some of them found their way into a magazine called The Honest Ulsterman. I also started writing my own poems, and some of them were published in the same magazine – but only when I passed them off as translations. Later, both translations (Tide and Undertow) and poetry (Cinema of the Blind) were published by the fledgling Blackstaff Press in Belfast. They sank pretty well without trace, but have been resurrected, edited and augmented on this website.

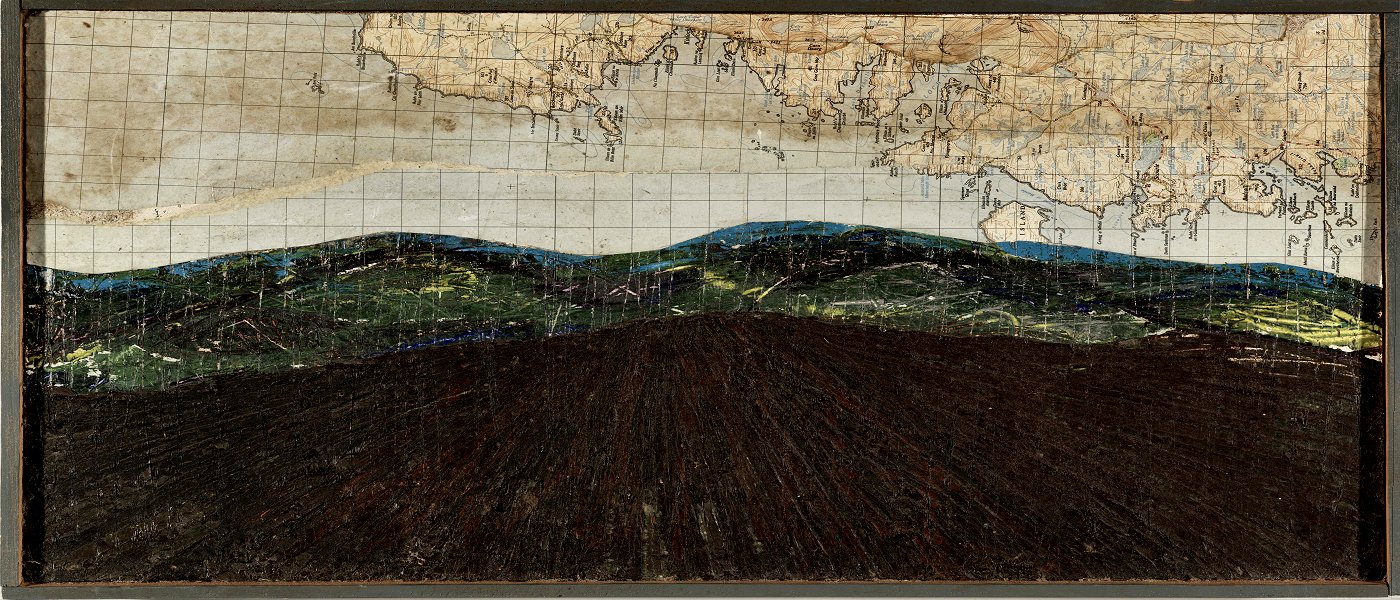

While I lived at Kilnatierney, my mother and I made many visits (in her car, at her expense) in search of prehistoric momuments all over Ireland, inspired by Evans' Field Guide and helped by the very kind Seán Ó Nualláin at the Archaeological Survey in Dublin. She greatly enjoyed the trips, some of which lasted a week, and one of which was during a snowy Christmas in Kenmare, county Kerry. I was in the vanguard of lay interest in these constructions, some of which, especially Portal Tombs, are wonderfully sculptural. The painting below is of a magnificent portal-tomb or dolmen at Kilclooney More, county Donegal – in a rainstorm. After ten years on the shore of Strangford Lough my £5 a week house and small garden was sold for expensive conversion, and I moved south to a larger, more remote two-storey stone-built farmhouse between Downpatrick and Strangford in the Barony of Lecale. This, too was £5 a week : the price of five loaves and two fishes at the time. It had a wonderful view over a rookery and fields to the Irish Sea and, often, the Isle of Man and even to Scotland. Behind it rose the Mountains of Mourne. It was soon after I moved to Loughkeelan (Loch Caolán: 'reedy lake,' not much larger than a pond), that my encounter in the crowded urinoir in the Centre Pompidou changed my life, and inspired many paintings, some of them landscapes,

This, and my lack of interest in polish and presentation amused one of my more perky lovers was William, who later made a name for himself as a totally differtent kind of artist in Dublin, before his early death. We visited each other frequently and had a lot of fun together. "My aunts" (Mattie and Girlie, then around 80) liked him very much. After my realisation that I was an enthusiastic pogonophile, I had not in any way excluded them from my life. I have always hated subterfuge, and one of the torments of school was that I hid my misdemeanours (hands in pockets, mitching or cutting 'games', being bullied) and misery from them. They visited every Sunday, and I called in on them frequently – especially when visiting lovers such as William in Belfast – for dinner, bed and breakfast. They liked most of my playmates, especially Pierre (above) the pastry-chef from Le Havre.

More paintings can be seen at : https://beyondthepale.pixieset.com/anthonyweirpaintings/ Selfportraits can be seen at: https://www.instagram.com/vieiloup/

|

|

|

|

this site only |

.

.