|

Translation and the Oulipo: The Case of the Persevering Maltese

reproduced from http://www.altx.com/ebr/EBR5/mathews.htm and presented in more readable form

This

essay was first presented at the French Institute in London in October,

1996

The word "Oulipo" is the acronym of the Ouvroir de litt´┐Żrature potentielle, or 'Workshop for Potential Literature', a group founded in 1960 by Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais. The group was created to explore what becomes possible when writing is subjected to arbitrary and restrictive procedures, preferably definable in mathematical terms. Since many have found this undertaking preposterous, it seemed useful to turn to translation and its attendant problems in making the interest of Oulipian methods clearer to skeptical writers and readers, as well as in examining the Case of the Persevering Maltese. Some of you may know the name of Ernest Botherby (born in Perth, Australia, 1869; died in Adelaide, 1944), the scholar who founded the Australian school of ethno-linguistics, and also the explorer who identified the variety of Apegetes known as botherbyi, popular in England during the years before the Great War when private greenhouses were still common. Botherby attained professional notoriety in the late '20s, after publishing several papers on a north New Guinean language called Pagolak. The peoples of New Guinea were a favorite subject with Botherby. He had begun studying them years before when, at the age of twenty-four, he undertook a solitary voyage into the interior of the island, vast areas of which remained uncharted at the time. A collation of reports by Nicholas von Mikhucho Maclay, the Reverend Macfarlane, and Otto Finsch had convinced young Botherby that tribes still existed in the New Guinean highlands that had shunned contact with their neighbors, not to mention the modern world, and preserved a truly primitive culture. Starting from Tagota at the mouth of the Fly, Botherby traversed the river by steam launch to a point over five hundred miles inland, whence he proceeded in more modest craft almost to its headwaters. After establishing a base camp, he traveled across the plains into the mountain forests, finally arriving at the unexplored region he was looking for, a complex of valleys lying--to use the toponymy of the time--between the Kaiserin Augusta, the Victor Emmanuel Mountains, and the continuation of the Musgrave Range. In one of these valleys Botherby discovered, as he had hoped, his first archaic tribe. He designates it as that of the Ohos. This community, numbering no more than a few hundred, lived a peaceable existence in conditions of extreme simplicity. They were hunter-gatherers equipped with rudimentary tools. They procured fire from conflagrations occurring in forests nearby but were incapable of making it otherwise. They also used speech, but a speech reduced to its minimum. The Oho language consisted of only three words and one expression, the invariable statement, "Red makes wrong." Having patiently won over the tribal chiefs, Botherby was able to verify this fact during the many weeks he spent with them. Other needs and wishes were communicated by sounds and signs; actual words were never used except for this unique assertion that "Red makes wrong." In time Botherby signified to his hosts a curiosity as to whether other communities existed in the region. The Ohos pointed north and east. When Botherby pointed west, he met with fierce disapproval. So it was naturally west that he next went, prudently distancing himself from the Oho settlement before taking that direction. His hunch was rewarded two days later when, in another valley, he came upon his second tribe, which he called the Uhas. The Uhas lived in a manner much like the Ohos, although they knew how to cultivate several edible roots and had domesticated the native pig; like the Ohos, they had a rudimentary language used invariably to make a single statement. The Uhas' statement was, "Here not there." They used it as exclusively as the Ohos used "Red makes wrong." Botherby eventually made his way back to the valley of the Ohos. There he was overcome by an understandable (if professionally incorrect) eagerness to share his second discovery, to wit, that near them lived a people of the same stock, leading a similar life, and possessed of the same basic gift of speech. As he was expounding this information with gestures that his audience readily understood, Botherby reached the point where he plainly needed to transmit the gist of the Uhas' one statement. He hesitated. How do you render "Here not there" in a tongue that can only express "Red makes wrong"? Botherby did not hesitate long. He saw, as you of course see, that he had no choice. There was only one solution. He grasped at once what all translators eventually learn: a language says what it can say, and that's that.

The range of the Oho and Uha languages is tiny; the range of modern languages, for instance, French and English, is vast. There is virtually nothing that can be said in English that cannot be said in French, and vice versa. Information, like phone numbers and race results, can easily be swapped between the two languages. Then again, some statements that seem informative do not really pass. A Frenchman says, "Je suis français;" an American says, "I'm American." "I'm French" and "Je suis am´┐Żricain" strike us as accurate translations. But are they? A Frenchman who asserts that he is French invokes willy-nilly a communal past of social, cultural, even conceptual evolution, one that transcends the mere legality of citizenship. But the fact of citizenship is what is paramount to most Americans, who probably feel, rightly or wrongly, that history is theirs to invent. The two national identities are radically different, and claims to them cannot be usefully translated in a way that will bridge this gap. I suggest that this gap extends into the remotest corners of the two languages. Elle s'est lev´┐Że de bonne heure means "She arose early," but in expectation of different breakfasts and waking from dreams in another guise. This does not mean that it's wrong to translate plain statements in a plain way, only that it is worth remembering that such translations tell us what writers say and not who they are. In this respect, French and English--or Germans and Portuguese--would seem to be as separate as Ohos and Uhas. There are also times when plain statements of fact do translate each other rather well--even the statements Je suis français and I'm American. To make what I mean clear, let me add to them one or two supplementary words. The Frenchman says, "Je suis français, Monsieur!" The American says, "I'm American, and you better believe it!" You see at once that the meaning of both statements is the same: an assertion not of nationality but of committed membership in a community--"my community." So even essentials can sometimes break through the linguistic separation. What makes this interesting is that the substantial identity of these statements does not lie in what they say--the information they contain is obviously not identical (French/American). So in this instance, at any rate, what has been successfully translated lies not in the nominal sense of the words but in other factors of language, whatever they may be. And whatever they may be, these factors are precisely the material of Oulipian experiment. So can the Oulipo help translators in their delicate task?

The Oulipo certainly can't help in an obvious way. Unless he wanted to sabotage his employer, an editor would be mad to employ an Oulipian as a translator. A few samples will show why. As our source text, let's take a famous line from Racine's Ph´┐Żdre:

The literal sense--please be charitable--is, "Here is Venus unreservedly fastened to her prey." First translation: I saw Alice jump highest--I, on silly crutches. Explanation: a rule of measure has been applied to the original. Each of its words is replaced by another word having the same number of letters. Second translation: "Don't tell anyone what we've learned until you're out in the street. Then shout it out, and when that one-horse carriage passes by, create a general pandemonium." Explanation: the sound of the original has been imitated as closely as possible--C'est V´┐Żnus tout enti´┐Żre ´┐Ż sa proie attach´┐Że / Save our news, toot, and share as uproar at a shay--and the results expanded into a narrative fragment. (Let me give you an example of a sound translation from English to French, Marcel Benabou's transformation of "A thing of beauty is a joy forever": Ah, singe d´┐Żbott´┐Ż, / Hisse un jouet fort et vert--"O unshod monkey, raise a stout green toy!") In these two examples the sense of the original has been quite forsaken. Even when they preserve the sense, however, Oulipian renderings hardly resemble normal ones. Third translation: At this place and time exists the goddess of love identified with the Greek Aphrodite, without reservation taking firm hold of her creature hunted and caught. Explanation: each word has been replaced by its dictionary definition. Last translation: Look at Cupid's mom just throttling that god's chump. Explanation: all words containing the letter e have been excluded. The preserved sense hardly makes these two translations faithful ones. And yet all four examples can be considered translations. What has been translated, however, is not the text's nominal sense but other of its components; and we may call these components "forms," taking "form" simply to mean a material element of written language that can be isolated and manipulated. So the first pair of examples are direct translations of forms: in the passage from one language to another, forms rather than sense are what is preserved (number of letters, sound). The second pair are replacements of forms--not only the words but a form of the original has been replaced, in one instance a lexical context, in the other the choice of vowels. These strange dislocations of the original may seem cavalier, but they are useful in drawing attention precisely to elements of language that normally pass us by, concerned as we naturally are with making sense of what we read. Nominal sense becomes implicitly no more than a part of overall meaning. Jacques Roubaud has recently provided a nice insight into its relativity in a discussion of the nature of poetry. He posits the axiom, "Poetry does not respect the principle of non-contradiction," and goes on to propose two poems for comparison (since Roubaud says they are poems, let's agree):

1st poem: This is a poem. There is, he asserts, no poetic contradiction between the two poems. I would add that according to ordinary criteria, the second poem is not a translation of the first; whereas by Oulipian criteria, they are perfect translations of one another - just as "Je suis français, Monsieur!" and "I'm American, and you better believe it" can be considered equivalents even though saying different things. This view of translation is a first clue to why the Oulipo has something to teach anyone interested in how writing and reading work.

The American novelist Robert Coover writes fiction that can be mildly described as outlandish. It is full of banal situations rapidly transformed into comic nightmares. No one would call him a realist. Yet at a literary conference several years ago, when he was asked why he wrote, he answered, "To tell the truth." His answer startled me; not that Robert Coover isn't an honest man, but this was not what his work first brought to mind. I quickly saw that he had been right to place himself in the age-old tradition of poetic truth-telling. In that case, we may then ask, why does he invent tales so unlike what we see around us? Why can't he simply say what is true? He could simply say it; what he cannot do is simply write it. We can tell the truth when we speak; it may not happen often, but you know it when it happens. But when you write down what you say, whether it's "I love you" or "Pass the salt," the words in themselves are no longer either true or untrue. No one is there to be responsible for them. Even in its ordinary, utilitarian uses, the written word cannot guarantee what it says. Can we agree that instruction manuals sometimes fail to help? Although once you've figured out your gadget, they become clear enough. Have the cooks among you tried out cookbook dishes that clearly had to be mastered before you could understand the recipe? The authors of manuals and cookbooks tell us honestly what they do, but because they aren't there to show us, it doesn't work. Consider the press. (If you watch your news, notice that the person on television speaks a written text.) What do we want from a news report? Hard information--what we call facts. And what are facts? What, for instance, is the central fact about a tennis match that you learn in a newspaper? The final score. Does that mean the score is the match? After three hours of play, Sampras and Agassi are tied two sets apiece and 4-all in the last set: where is the final score? Nowhere to be seen. The score only comes into existence when the match passes out of existence. Facts are the score, not the game. Facts are lies. Not because they are false, but because facts belong to the past--to what was, never to what is. We love them, because once reality is safely lodged in the past, it becomes reassuring, reasonable, and easy to manage. Or at least easier: we read, "50 Palestinians and 12 Israelis killed in renewed fighting," barely gulp, and turn the page. Naturally. That is the way written language naturally works. Our language is made up of devices called sentences and paragraphs that automatically produce reasonable conclusions, which is another word for facts. There is no escaping this. It is not a Bad Thing. However, a reality we can call the truth must be looked for elsewhere.

Fragment

of a neosocratic dialogue.

Scene: outside the wall of Athens You have been silent for a long time, Socrates. I have been observing these little statues, Echecrates. This shady spot must be dedicated to Proteus. I thought that you might be falling asleep. The breeze is so soft, the brook makes so lulling a sound, and then the air is filled with such a sweet scent of wild thyme. It is abundant enough and makes a pleasant couch; but I am not sleepy, Echecrates. All the same, you seem little inclined to speak. Perhaps. So you prefer silence, Socrates? Let me listen to you, Echecrates. Will you agree to consider a question, one that you, better than anyone, can surely answer? What is your question? Echecrates, tell me: what is the truth? Socrates, I expect you wish for silence after all, and that you hope to keep me quiet with your proposal. I shall not let you off so easily but answer your question forthwith. The truth is the perception of Ideas, which are the sole causes of all things and the sole objects of knowledge. Your answer, Echecrates, is apt; for certainly the knowledge of truth requires the perception of Ideas. And yet the truth is not that. In that case, Socrates, let me modify my answer, for I see that the truth lies of course not in perceiving but in what is perceived: the truth, then, is the divine array of absolute forms by which the One is manifest in the Many, and the Many subsumed in the One. What you say is by no means false, since no opinion of the truth can deny its unity or exclude its multiplicity. And yet, Echecrates, the truth is not that. If only I could guess what you expect of me! Socrates, you have turned me into a confused child standing before a stern and patient father, hoping to please and dreading to disappoint him. Let me try once more to satisfy you. The truth is what is apparent only to the dead, whose immortal souls are freed from the hindrance of the bodily senses and are at last capable of knowing the pure and the good. Let us hope, Echecrates, that we two are carried to that realm of virtuous souls, where we shall converse with Orpheus and Homer and know ourselves at last. But I feel that my question wearies you, and that the time has come to put it aside. Only in conclusion, let me repeat what I said before: the truth is not that. But is there an answer to your question, Socrates? Yes, and I have given it to you. Socrates, I do not understand. I have given you the answer three times. The truth is: not that. Is not this so, Echecrates? However you define it, whatever words you assign to it, you can and must always say afterwards, the truth is: Not that.

Keep moving

If Neosocrates is right, saying that the truth is "not that" implies: whatever you think you know, don't stop there. How can this apply to what has already been said? Earlier I reached the conclusion, facts are lies. What if I round that out: facts are lies--and that's a fact. Look at what happens now. Fact's are lies, and that's a fact: if the statement "facts are lies" is a fact, then the statement is a lie; and if it's a lie, then facts aren't lies. But in that case the fact that facts are lies is a lie, and so saying that facts are lies is not a lie, and so facts are in fact lies, and the statement "facts aren't lies" is a lie--and that's a fact. And so on and so on. This modest circular paradox has its interest. First of all, when we read or hear it, something occurs beyond what's being said. Second, what was previously a conclusion becomes a continuum, a succession of events rather than a single event. What is the main difference between a conclusion and a continuum? What distinguishes the final score of a tennis match from the moment when Agassi and Sampras are tied 4-all in the fifth set? Uncertainty and movement; in a word, change, a quality that is wholly wanting in the realm of facts. Change can have no place among facts, which constitute the realm of fatality, of what's over and done with. The realm where change exists is that of possibility. "Not that" suggests that truth is a continuum of uncertain possibility. It only exists in the next now. In writing, that means the now of reading. Since the first reader is the writer herself, a truth-telling writer has to create the possibility of not yet knowing what the truth is, of not yet knowing what he or she is going to say. Non-writing artists seem seem to grasp this easily. Francis Bacon described his painting as "accident engendering accident." Ornette Coleman said he never knew what he was going to play next until he heard the note coming out of his saxophone. One writer, at least, made the point neatly: when the Red Queen tells Alice to hurry up and say what she thinks, Alice replies, "How can I say what I think till I see what I say?" If we think of writers as translators, what they must translate is not something already known but what is unknown and unpredictable. The writer is an Oho who has just heard what the Uhas say. Poor Botherby couldn't begin to cope: he wanted to report a fact when what he needed was a cultural revolution. Fortunately, we have the necessary means, not always revolutionary. Language creates a continuum of its own, precisely in those components that concern not the plain sense of words but what we noticed in the circular paradox, the movement that their sequence engenders.

Translation and The Oulipo (2) If truth is a changing continuum and not a series of discrete events and ideas, it's unlikely that we can catch up with it in any reasonable way. Reasonable and honest accounts will always resemble superior instruction manuals, useful, even fascinating, never the thing itself. Or perhaps we should say a thing itself. On the page, truth begins when something real happens. Imaginative writers officially disclaim reasonableness and honesty. That's what imaginative (or creative) signifies: they're lying. Poets and novelists are outright liars. They promise to provide no useful information unless they feel like it. Three advantages accrue immediately. First, you are released from all responsibility to the dead world of facts. Second, your readers are ready to believe you, since by admitting you lie, you've told the truth at least once. Third and best, you can discover the unforeseen truth by making it up. You are condemned to possibility: you can say anything you like. So much freedom can be unnerving. If you can say anything, where do you start? You have already started. No one sits down to write in the abstract, but to write something. Some writerly object of desire has appeared, and you are setting off in pursuit of it. The object may be an anedcdote, an idea, a vision, an effect, a climate, an emotion, a clever plot, a formal pattern--it doesn't matter, it is what you're after. What happens next? The process of translation as it is commonly practiced provides a helpful analogy. I am speaking from my own experience, but I do not think it exceptional. Simplistically described, translation means converting a text in a source language into its replica in a target language. Both translators and readers know what happens when this process is incomplete: the translator becomes so transfixed by the source text that when he shifts to his native tongue he drags along not only what should be kept of the original but much more--foreign phrasing, word order, even words. The results hang uncomfortably somewhere between the two languages, and a brutal effort is needed to move them the rest of the way. I learned how to avoid this pitfall. When I translate, I begin by studying the original text until I understand it thoroughly. Then, knowing that I can say anything I understand, no matter how awkwardly, I say what I have now understood and write down my words. I imagine myself talking to a friend across the table to make sure the words I use are ones I naturally speak. It makes no difference if what I write is shambling or coarse or much too long. What I need is not elegance but natural, late-twentieth-century American vernacular. Translating the opening sentence of Proust--Longtemps je me suis couch´┐Ż de bonne heure--I might write down: When I was a kid, it took me years to get my parents to let me even stay up till nine. (This is actually mid-twentieth century vernacular; but that's where I'm from, and it's what I might say.) There is still work to do. But I have gained an enormous advantage. Instead of being stuck in the source language, I am standing firmly on home ground. My material is as familiar as anything in language can be; and instead of having to move away from the foreign text, I can now move towards it as I improve my clumsy rendering, sure that at every step, with the source text as my goal, I shall be working in native English. All I have to do is edit my own writing until I eventually reach a finished version. Think of the writer's object of desire--vision, situation, whatever--as his source text. Like the translator, he learns everything he can about it. He then abandons it while he chooses a home ground. Home ground for him will be a mode of writing. He probably knows already if he should write a poem, a novel, or a play. But if it is a novel, what kind of novel should it be--detective, picaresque, romantic, science fiction, or perhaps a war novel? And if a war novel, which war, seen from which side, on what scale (epic, intimate, both)? At some moment, never forgetting his object of desire, which may be the scene of a thundershower breaking on a six-year-old girl and boy, he will have assembled the congenial conventions and materials that will give him a multitude of things to do as he works towards realizing that initial glimpse of a summer day, a storm, and two children. An example can make this clearer. Throughout his life, Robert Louis Stevenson was fascinated by the dual personality. His greatest exploration of the theme was The Master of Ballantrae, but he tried other ways of approaching it. In one instance he chose as his home ground the 19th-century penny dreadful with its array of melodramatic and grotesque trappings. Stevenson saw that to discover the mystery of his object of desire--the dual personality--in its starkest terms, these trappings provided what he needed. They proved so suitable that we scarcely notice them when we read Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a work successful enough to have attained the status of a modern legend. It would be interesting to investigate works whose home grounds are not so readily discernable; it would also be laborious, and it is now time to think about the Oulipo.

Back home at the Oulipo Since the mid-19th century, writers have chosen their home grounds more and more outside the main traditions of fiction and poetry. Firbank used the brittle comedy of manners to register his tragic views; Kafka turned to the parable, Hofmannsthal and Calvino on occasion to fairy tales, Henry Miller to pornography. Other writers invented their own home grounds - Mallarm´┐Ż in poetry, for instance, Joyce and Raymond Roussel in fiction--and it is for their successors and their readers that the Oulipo has a particular relevance. A parenthetical point: the Oulipo is not a literary school. It is not even concerned with the production of literary works. It is first and last a laboratory where, through experiment and erudition, possibilities of writing under arbitrary and severe restrictions are investigated. The use of these possibilities is the business of individual writers, Oulipian or not. All the same, several members of the Oulipo have exploited Oulipian procedures in their work. I suggest that these procedures have provided them with home grounds. How is this possible? How can methods based on deprivation become the comforting terrain on which a writer sets out in pursuit of an object of desire? Why would anybody not a masochist want to determine a sequence of episodes according to the tortuous path of a knight across the entire chessboard? Or use the graphic formulations of a structural semiologist to plot a novel? Or limit one's vocabulary in a story to the threadbare words contained in a small group of proverbs? Or, if a poet, why write using only the letters of the name of the person the poem addresses? or conversely exclude those letters successively in the sequence of verses? or create a poetic corpus using the ape language of the Tarzan books? Nevertheless, these are some of the things Perec, Calvino, Jacques Jouet, and I chose to do, with acceptable results. Why did we do them? I used to wonder myself. When I first learned that Perec had written a novel without using the letter e, I was horrified. It sounded less like coming home than committing oneself to a concentration camp. When we were children, what we loved most was playing. After a fidgety family meal or excruciating hours in class, going out to play made life worth living. Sometimes we went out and played any old way; but the most fun I had was playing real games. I have no idea what games you enjoyed, but my own favorites were Capture the Flag and Prisoner's Base--hard games with tough rules. When I played them, I was aware of nothing else in the world, except that the sun was getting low on the horizon and my happiness would soon be over. In Manhattan last autumn, I stopped to watch a school soccer game in which an eight-year-old girl was playing fullback. She was alertness personified, never taking her eye off the ball, skipping from side to side in anticipation of the shot that might come her way. She had definitely not engaged in a trivial activity. The Oulipo supplies writers with hard games to play. They are adult games insofar as children cannot play most of them; otherwise they bring us back to a familiar home ground of our childhood. Like Capture the Flag, the games have demanding rules that we must never forget (well, hardly ever), and these rules are moreover active ones: satisfying them keeps us too busy to worry about being reasonable. Of course our object of desire, like the flag to be captured, remains present to us. Thanks to the impossible rules, we find ourselves doing and saying things we would never have imagined otherwise, things that often turn out to be exactly what we need to reach our goal. Two examples. Georges Perec's novel without the letter e, intermittently dramatic, mysterious, and funny, describes a world filled at every turn with multiple disappearances. Some undefined and crucial element in it is both missing from it and threatening it--something as central as the letter e to the French language, as primordial as one's mother tongue. The tone is anything but solemn, and yet by accepting his curious rule and exploring its semantic consequences, Perec succeeded in creating a vivid replica of his own plight--the orphaned state that had previously left him paralyzed as a writer. I had a similar experience with my novel Cigarettes. My "object of desire" was telling the story of a passionate friendship between two middle-aged women. That was all I knew. I had concocted an elaborate formal scheme in which abstract situations were permutated according to a set pattern. This outline suggested nothing in particular, and for a time it remained utterly empty and bewildering. It then began filling up with situations and characters that seem to come from nowhere; most of them belonged to the world I had grown up in. I had never been able to face writing about it before, even though I'd wanted to make it my subject from the moment I turned to fiction. It now reinvented itself in an unexpected and fitting guise that I could never have discovered otherwise. For Perec and me, writing under constraint proved to be not a limitation but a liberation. Our unreasonable home grounds were what had at last enabled us to come home.

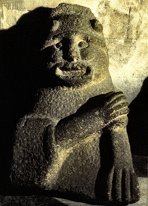

The Case of the Persevering Maltese Earlier I quoted Francis Bacon describing his painting as "accident engendering accident." Imposing fixed patterns as it does, the Oulipian approach sounds as though it discouraged such self-generating activity, but this is not so: in practice it guarantees that the unforeseen will happen and keep happening. It keeps us out of control. Control usually means submitting reasonably to the truly tyrannical patterns that language imposes on us whether we like them or not. Language by its nature makes us focus on its conclusions, not its presence. Oulipian dislocations of this "natural" language counter its de facto authority or, at the least, provide an alternative to it. Don't forget that language cares as little about our individual needs as the tides and the winds; ill-equipped, we can affect it no better than King Canute. Those of you who have visited Venice may know the paintings of Vittore Carpaccio in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni. The schiavoni were slavs, and the cycle of paintings concerns a patron saint of Dalmatia, St. Jerome. Surprisingly, St. Jerome is absent from the most beautiful of these pictures, "The Vision of St. Augustine;" but there is a good reason for this. St. Augustine sits at his desk, where he has just finished reading a letter from St. Jerome asking his advice on a theological matter. St. Augustine has scarcely taken up his quill to reply when light floods his study and a miraculous voice reveals to him that St. Jerome is dead. It might be entertaining to speculate on the relevance of the scene to what I've been discussing--pointing out, perhaps, the futility of the reasoned answer St. Augustine is preparing in the face of the unforeseen and overwhelming truth. But let's not. We have a still more entertaining object to contemplate. In the middle of the floor to the left of the saint's desk, a little Maltese dog sits bolt upright. He is bathed with celestial light, to which he pays no attention as he stares at his master in an attitude of absolute expectation, as alert in his immobility as was my little fullback in her agile skipping. He is as unconcerned by the momentous event now occurring as he is by literary theory. His attitude might be translated as the human question, What next? Like children and Oulipians, he probably wants to play, but he can't be sure of that or anything else. He has to wait to find out. What next? What next, and what after that? The answer will be something like the one given by Marcel Duchamp when asked what he considered the highest goal of a successful life. He replied, "It. Whatever has no name."

Harry Mathews has published many books of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry; his most recent novel is The Journalist (Godine). A member of the Oulipo since 1972, he co-edited thenOulipo Compendium, an archival work published by Atlas Press in 1997.  Copyright ´┐Ż 1997 ebrand the author. All rights

reserved.

Copyright ´┐Ż 1997 ebrand the author. All rights

reserved.

riPOSTe:[email protected] |