anticopyright

2019

Anthony Weir

|

GRISHA

PERELMAN

Dr

Grigori Yakovlevich Perelman, 44, said

through the closed door: They

both share her $75-a-month pension Neighbours say his trousers are always too short for his legs. The

Millennium Prize was given in 2006 which

he posted in 2002 as a terse paper to an online archive, At

the time he stated: "I'm

not a hero of mathematics. "If the proof is correct then no further recognition is needed. "I

do not think anything that I say can be

"We

are trying to get rid of cockroaches in our block, Dr

Perelman once said to an American journalist:

Dr

Perelman is also a talented violinist. In

March 2010, it was announced that he was the first person The

Poincaré

Conjecture was more than 100 years old

|

Would Dr

Perelman have been understood and appreciated by the American writer

and columnist

S.J. Perelman ?

|

"..Why

can't they stop clucking, and just push the money

Disillusioned with the world around him, he effectively withdrew from society about five years ago, taking a monk-like vow of silence. Eventually, he stopped answering e-mails. It was not always thus. Grisha, as he is known to his friends, was born in 1966 in what was then known as Leningrad at a time when the Soviet Union was at the peak of its powers. His mother, Ludmila, was a talented mathematician in her own right, and his father Yakov, who now lives in Israel, was a prominent engineer. Both suffered racial discrimination. The young Grisha's talents were noticed before he had reached the age of 11. He was enrolled at an élite school specialising in maths, was pushed hard to excel, and as a school child in the 1980s won two nationwide maths competitions. "In 1981, he became the best of his age-group in the Soviet Union," recalled Sergey Rukshin, the director of the élite maths school where he studied. Rukshin remembers how at the age of 14 Perelman devoted himself wholly to maths - even putting aside his beloved violin. "It was very important for him to be Number One," he said. Soviet distrust of Jews was strong at the time and the boy prodigy had to swim against a powerful tide of anti-Semitism. "It was a horrible time for Jewish people," said Mr Rukshin. "Grigori is pure Jewish and I never minded that - but my bosses did. When they found out I had invited him to study at our maths centre they reprimanded me for incorrect ethnic politics." Top academics would express indignation when seeing his overtly Jewish surname in competition lists. Somehow, Grisha managed to shake off the perceived stigma and went on to get a PhD at Leningrad university before securing a good position at a top academic institute. In the late 1980s and early 1990s he achieved what many penniless Russian academics dreamed of and moved to the United States to conduct research at top universities. Colleagues in the U.S. remember his fingernails being unusually long, his eccentricity, and the modesty of his lifestyle. Even though he was well paid, they say his fridge contained little more than milk and bread. [Actually black bread and kefir, or fermented milk, a fairly healthy diet.] In 1995, he shocked his peers by returning to the poorly-funded research institute in his native St Petersburg where he had earlier worked, turning down lucrative offers in the US in favour of a tiny salary worth the equivalent of £120 a month. He had been uninterested in churning out routine yet pedestrian academic papers and determined to focus on solving a complex maths puzzle known as the Poincaré conjecture, that had baffled mathematicians for more than a century. But it seems his new colleagues lost patience with him. "He did not want any distractions but the scientists at the institute are forced to publish academic papers every two or three years," recalled Tamara Yefimova, one of his former maths teachers. "Grigori did not want to waste his time on this and colleagues voted him out. They voted out the most brilliant mathematician in the world." Distraught, Mr Perelman left under a cloud in December 2005 and appears never to have worked since. The director of the institute, Dr Ildar Ibragimov, denies Dr Perelman was forced out. Though he admits colleagues found him difficult, he claims Dr Perelman left of his own accord. "Some of his colleagues thought he was odd [but] I don't think it was jealousy for his achievements. Grigori demanded a lot of himself but also from people around him. This made him a difficult person to deal with." By the time he began to be feted and lavished with prizes and invitations to speak at top academic conferences, he had turned in on himself. People who know him say he and his mother live off her modest pension and money sent monthly by his sister, who lives in Sweden. His old mentor, Mr Rukshin, says people should respect his choice. "Believe you me, a beard does not make a man mad or abnormal," he said. "The prize was never his purpose. He was interested in work, not in money." Neighbours say his trousers are always too short for his legs, and that the balcony to his flat has been left to rot. Every day they see him walk to a grocery shop at 1.30 pm where he buys the same things: eggs, cheese, spaghetti, sour cream, black bread and a kilo of oranges. It

is not clear whether he still practises mathematics. He is thought

to pass the time by playing ping-pong against the wall of his

flat.

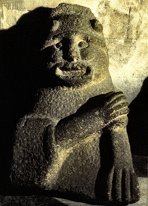

Saint Vassily (Basil) of Moscow,

|