The

Bektashi Order of Dervishes

Anthony Weir

To

read this page properly, please ensure that the character encoding

of your browser is not set to the default 'Unicode'.

For those who have Awareness,

a hint is quite enough.

For the multitudes of heedless

mere knowledge is useless.

-

- Haji Bektash Veli

|

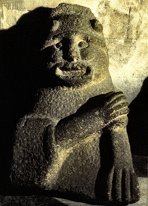

The

depictions of Bektash with a lion

|

The 'heretical' Sufi Bektashi sect offers the conscientious the nearest to the way of life that Jesus of Galilee led (and hoped his followers would lead) that is institutionally possible for 'Christianity' or Islam in the 21st century. Like Jesus and his followers, Bektashi are a celibate, commensal, anti-hierarchical, anti-dogmatic, anti-hypocritical Brotherhood who do not exclude women, but who do stand against those vile "Family Values" that were the curse of ancient world as of the modern, and were reviled by Diogenes of Sinope whose nihilist tradition Jesus of Galilee - alongwith scores of other dissidents - briefly followed and briefly perpetuated before being betrayed by his own disciples. They are closely-connected with the popular and tolerant Alevi sect in Turkey, who also venerate Haji Bektash Veli. The history of the Bektashi is curious: just as 'Christianity' quickly became associated with Roman imperialism and ever since then an intolerant instrument of oppression, the Bektashi were associated with Turkish imperialism. And just as Jesus was almost trapped into becoming a pawn for Jewish nationalism, Bektash was associated with an anti-Seljuk movement... |

|

The constantly recurring migrations across Central Asia brought not only Celts and Huns, Mongols and Turkish tribes but thoughts and artifacts from China and India, and spiritual leaders in the classic Eastern form of wandering holy mystics. The tradition of monasticism and Desert Sainthood in the Christian West owed more to influence from India through Afghanistan than from ancient Greece. The philosophies of Sufi and heterodox Christian mystics share basic attitudes with Tao and Zen. Teaching mystics (such as Jesus of Galilee) often were credited with miraculous powers amongst Muslims, Christians and 'pagans' of all sorts. Haji Bektash Veli was such a teacher, and like most, made a stand against hypocrisy, intolerance and obsession with ancient texts and rules. Sufism is not a sect, but a tendency. Sufis can be Sunni or Sh'ia. Sufism is an individual and individualistic path to direct experience of God (or 'Ultimate Reality', for Sufism has strayed rather far from orthodox. patriarchal Islam) through love and integrity, and not through the automatic rituals of the pious (who are so often impious). This non- or anti-egotistical path usually involves dissociation or detachment from 'normality', from getting-and-spending, career and family. The Sufi saint (or Dervish) is remarkably like Diogenes of Sinope, Jesus of Galilee or Hindu Sadhus - and indeed orthodox Muslims often accuse the Sufis of having been infected by Christianity (in its raw rather than Roman state) on the one hand, and by Hinduism on the other. This accusation, of course, ignores the fact that there are innumerable sects in both these religions. Sufis see God not as a remote and solitary patriarch but as divinely lovable. Love in all its forms is at the centre, and the love is expressed (as love must be) either in mystical poetry (such as that by Rumi), or supra-verbally - by music and dance: anathema to the more frighteningly-fundamentalist Muslims such as the Wah'habis. Music and dance easily lead to trance in which Sufis experience ecstasy which they consider to emanate from God or Perfection. In Pakistan and India this is modelled on Hindu Kyal and is known as Qawwali. Many Sufis are wanderers, like Hindu Sadhus, and Bektash Veli was a fairly typical travelling ascetic or Dervish, held by hagiographic sources to have been a Turk from Khorasan (or Qurasan: North-eastern Iran and Western Afghanistan where Omar Khayyám also came from over a hundred years earlier). Bektash was a follower of the Sufi Shaikh Ahmet Yesewi who died in 1166, at a time when the Crusader wars and raids were occurring far to the West. Tradition has it that, on the command of his spiritual master, he flew from his native land in the form of a dove, to Rum (the name then given by Turks and Persians to formerly-Byzantine Anatolia) in 1281, after the Mongols had destroyed the Seljuq state and the vestiges of the Caliphate. He 'landed' at present-day Hajibektash, a village near Kirsehir in Cappadocia - an area which, in the middle Byzantine era, was a centre of Paulinians: heterodox mystic Christians who gave rise to the Bogomils and later the Cathars and Swedenborgians. He was one of those who helped to synthesise the pre-lslamic religious and shamanic elements that still prevailed in Turkic beliefs with more puritanical, orthodox Islam - which hated what it saw as primitive magical practices. The Babas' influence was enormous and rivalled that of the military leaders and the prestige of the Seljuk rulers. These, although Turkic, had adopted aspects of Iranian culture. Like many dervishes from the East, Haji Bektash was evidently a mouthpiece for the social grievances of the Turkic tribesmen - for he was involved in the social upheaval against the (Sunni) Seljuk rulers headed by a certain Baba Ilyas (circa 1240). Haji Bektash

is reputed to have conferred his special protection on the Janissaries

before he died in 738/1337.

The

Bektashi Sect and the Janissaries The Janissaries ("new soldiers") were élite infantry units originally formed by Sultan Murad I around 1330 from renegade prisoners and the non-Islamic (almost-always Christian) children exacted as tribute by Turkish conquerors. They corresponded to modern gendarmerie or carabinieri (except that they were not allowed to take wives or Muslim whores) and wore special white felt headgear, mounted on a metal headband and hanging down the back, which was supposed to represent Haji Bektash's sleeve. They were sometimes called 'Sons of Haji Bektash', Haci Bektas Ogullari - and Sultan Selim III, in appealing to the Janissaries to be loyal and brave in the second year of his reign (1789), addressed them as the Knights of Haji Bektash, Haci Bektas Köçekleri. One consequence of the intimate Bektashi association with the Janissaries and hence with Ottoman authority was that the Bektashis were rarely attacked on grounds of doctrine or innovations. They were very much influenced by the chivalric code that pervades the teaching of Mansur al-Hallaj, famous Sufi martyr-mystic who became not only a symbol for those who seek God but also for those who have been imprisoned or tortured by unjust governments. The “gallows of Mansur” (a mock execution) was part of the initiation rite of the Bektashis; moreover, to refer to Mansur's Gibbet was very common among Bektashi poets, especially the ones affiliated with the Janissary army. The Bektashis are a syncretic and eclectic (some would say heretical and egregious) sect, with Christian and oriental elements, rather as the Sikhs combine elements of Hinduism with Islam. The 'heretical' Shi'a doctrines and ritual of the Bektashis do not actually derive from Hajji Bektash, though there is no need to assume that he was any more orthodox than other babas. The order grew out of saint-veneration and a monastic, commensual tradition combining elements from many sources both esoteric (Eastern) and popular: the Turkish, pre-Turkish/Byzantine and pre-Christian traditions of Anatolia. Their belief in the brotherhood of man (and woman) is illustrated by the following verse by the Turk Yunus Emre (see below) who died before Haji Bektash: Let us all

be friends for ever During the fifteenth century when Bektashism was developing into a comprehensive organization, it incorporated various ideas and beliefs - from 'Christianity', the qizilbash (redheads) of eastern Asia Minor and Kurdistan, and folk-ideas from nomadic and village groups - alevis, takhtajis, etc. Bektashis proper belong to a lodge or tekke (teqë in Albanian). Probably the first leader of organised Bektashism was Balim Sultan (died 922/1516), whose title is Pir Sani, the Second Patron Saint. Pir, a Persian word meaning 'lord', is a title applied to the heads of Sufi orders. 'Sufi' itself means 'wool' - after the rough woollen robe that the early Sufis wore. Bektashi Babas (celibate spiritual advisers) accompanied the Janissaries as chaplains. In becoming enrolled as members of the élite Janissary Corps a vow of faithfulness to the Way of Haji Bektash was extracted from each soldier. The recognition, however, of Bektash as Patron Saint and the formal acceptance of various charitable and ascetic doctrines did not do much to 'spiritualise' the Janissary way of life.

|

. . |

I tie up greed,

and release generosity.

I shackle anger, and liberate meekness. I bind consumerism, and unbind piety. I tie up ignorance, and unfetter respect for the Absolute. I restrain passion, and release the love of the Absolute. I tie up desire, and free fulfilment. I bind commoditisation, and liberate awareness. |

|

THE DECLINE AND EXILE OF THE BEKTASHIS In 1808 Selim III's younger cousin Mehmet II, came to the throne. He understood the danger posed by the highly-conservative Janissaries, and felt that the survival of the Ottoman Empire depended on suppressing them - and the Bektashi Order as well. For centuries the Bektashi Order controlled the most productive and lucrative salt mines in the Ottoman Empire; the salt from those mines was called Hajji Bektash Salt. Bektashi properties were turned over to Naqshbendi dervishes. It was alleged that Mehmet II vowed to behead seventy thousand Bektashis, and that when he could not find that many to execute he ordered the headpieces to be cut off Bektashi tombstones until the count should be complete! Since the Bektashi were extremely heterodox - even eating pork - the more orthodox Islamic (especially Sunni and non-celibate) clergy helped enthusiastically with the persecution of a sect seen as not only as militaristic by ordinary people but as morally dangerous by the devout. This parallels the earlier European suppression of the Knights Templar - who also were associated with special buildings: circular churches. Ironically, while the Janissary Corps were strongly anti-reformist, the unorthodox, dissident, antinomian ideas of the Bektashi connected with the liberal thought of the philosophers of 18th century France. As a result, the Bektashi could establish loose contacts with one of the networks that carried the ideas of the 18th century philosophers: the Freemasons. Many active politicians in Istanbul either were or were connected with Freemasons during the 19th century when both French and English Lodges were established in Istanbul. Membership increased in the last years of the 19th century - especially among the group of opponents to Sultan Abdulhamid II (1876-1909) known as the 'Young Turks'. It must be emphasised, however, that what mysticism that survives in modern Freemasonry is as false as Christmas, whereas the Bektashi are a genuine mystical fraternity. The Bektashis were not wiped out - but took over the Naqshbendis. With savage irony, the last or 'anti-Sultan', son of an Albanian mother, the revolutionary Westernising-democratising fascist Mustafa Kemal, who wanted to be known as Atatürk (Father of the Turks), successfully banished the entire Bektashi community and movement to Albania - the only predominantly Muslim country in Europe, unique in its acceptance of various religions, sects and ethnicities. ("The only religion of Albanians is Albania".)

Unknowing Unknowing Unknowing Knowing,

THE

BEKTASHIS, ALBANIA AND ORHAN PAMUK'S BLACK BOOK "It was six years ago," Saim said, "a Saturday afternoon. I was leafing through the magazines put out by fellow-travellers of the Albanian Workers' Party and its leader Enver Hoxha. There were three Turkish publications back then which all denounced each other vitriolically. I was scanning the last issue of one called LABOUR OF THE PEOPLE to see if there was anything interesting in it. I noticed a photograph and an article about a ceremony in honour of new recruits inducted into the splinter-group. What caught my attention was not the revelation that here was a Marxist outfit with songs and poems in a country where all Communist activity is banned - but the caption that deliberately mentioned the Twelve Columns in the black-and-white photo which showed a crowd smoking passionately as if it were performing a sacred duty, posters of Enver Hoxha and Chairman Mao, and reciters of poetry. Even more strange, the assumed names of the new recruits were chosen from the names of the 'Alawite Sufi order - names like Hasan, Hüseyin (Hussain), Ali and (as I was later to discover) the names of the Bektashi shaikhs or spiritual leaders. Had I not known that the Bektashi had been big in Albania between the wars, I would perhaps never have suspected anything about this incredible mystery, and, after four years of reading all sorts of books on the Bektashi, the Janissaries, Hurufism and Albanian Communism, I discovered a hundred-and-fifty-year-old conspiracy. "You know all this anyway," said Saim - but went on to recount the seven-centuries' Bektashi history, beginning with Haji Bektash Veli. He described how the order has 'Alawite, Sufi and Shamanistic origins, how it was related to the periods of formation and rise of the Ottomans and the tradition of revolution and rebellion in the Janissary Corps. When you consider that every Janissary was a Bektashi, you understand how the important the Order was. The first time they got the boot from Istanbul, it was because of the Janissaries: while the barracks was bombarded in 1826 under the orders of Mehmet II who lost patience with the Janissaries' resistance to his Westernising programme of reform. The tekkes were shut down and the Bektashi dervishes kicked out. Twenty years after going underground, the Bektashis returned to Istanbul, but this time under the guise of the Naqshbendi order. Until Atatürk proscribed them completely seventy years later, the Bektashis presented themselves to the world as Naqshis - but amongst themselves they were Bektashis. Galip studied an engraving from an English travel book that represented a Bektashi ritual which probably reflected the fantasy in the mind of the artist-traveller than reality. He counted the Twelve Columns in the engraving. "The third time the Bektashis manifested themselves," Saim said, "it was fifty years after the Republic was declared in Turkey - not under the Nakshbendi order this time but wearing a Marxist-Leninist guise..." Following a silence, he gave an excited recital, producing as illustration articles, photos, engravings he had cut out of journals, books, leaflets. All that was performed, written and experienced in the Bektashi order corresponded exactly to all that went on in the political factions: the rituals of initiation, the periods of severe trials and self-denial before initiation; the pain endured by the young aspirants during these periods; the veneration of the fallen, the sainted and the dead amongst the order's or faction's past members, and the rites of paying homage to them; the sacred meaning assigned to the word Road [spiritual path]; the repetition of words and expressions for the sake of the spirit of oneness and community; the litanies; the fact that Adepts who travel the same road recognise each other by their beards and moustaches - even the expression in their eyes; the rhyme-scheme and metre in the poems they recited and the songs they played in their ceremonies, etc. etc. "Ostensibly, unless all this is only coincidence," said Saim, "unless God is playing a cruel epostolic joke on me, then I'd have to be blind not to see that the logogriphs and the anagrams the Bektashis took over from the Hurufis are, without any doubt, being reiterated in the leftist publications." In the silence that followed - broken only by the whistles of the nightwatchmen in outlying quarter - Saim slowly began to recite for Galip the word-games he had worked out, presenting them with their secondary meanings, as if he were repeating his prayers. The kids who joined political factions, Saim went on to say, had no idea they had turned Bektashi. Since the whole thing was concocted between the party middle management and the Bektashi masters in Albania, those in the rank and file were entirely unaware that their photos taken at the ceremonies, rituals, marches and meals, were all evaluated by some dervishes in Albania as an extension of their Order. Towards morning, as Galip drowsed on the sofa, Saim was still soliloquising that, in all probability, the elderly Bektashi masters in Albania who got together with the Party leadership in the dreamlike empty ballroom of a white Italian hotel left over from the turn of the century, looking through tearful eyes at the photos of the Turkish youths, had no inkling that it wasn't the mysteries of the order that were being recited at the ceremonies, but enthusiastic Marxist-Leninist analyses. (selected from Orhan Pamuk's Black

Book) |

The essence of Sufism is learning

to do without Desire, or Envy,

or Achievement of anything more than Humility.

|

Azmî

|

A European engraving (1868) of a Bektashi Dervish |

|

During the 2nd century of the Christian Era, Illyria (part of which is modern Albania) was Christianised. In 732 Pope Gregory III placed the Albanian churches under the leadership of the patriarch of Constantinople. The Christians became part of the Eastern Orthodox church. In 1054, following the Schism between the Eastern and Western churches, there was a split in the Albanian church. Southern Albania remained associated with Constantinople, and northern Albania reunited with Rome. Then, in the 15th century, the Turks introduced Islam. The Turks viewed Roman Catholics as a threat to their rule. Catholics were required to pay a high tax. Some converted to Islam, but some chose to leave Albania - such as the Arberësh who settled in Southern Italy. A few Catholic "crypto-Christians" pretended to be Muslims in public to escape the taxes, while continuing to practise the Catholic faith in their home. But most Albanians became Muslim. Before the outlawing of religion in 1967, Albania's population was 75% Muslim, 15% Orthodox Christian and 10% Roman Catholic. An Albanian-American source says that the Muslim population was further divided between the 85% who followed the Hanafi school of the Ahli-Sunnah wal Jama' and the 15% who were Bektashi. Other sources say that most Albanian Muslims were Bektashi, but by this they probably meant Naqshbandi or Haqqani, other Sufic sects with whom they were confused. Since the Bektashi are celibate, lay people with families cannot be Bektashi. The majority of Albanian urban dwellers were found to be Muslim, and most of central and northeast Albania was populated solely by Muslims. Catholics were found primarily among the inhabitants of the extremely mountainous northwestern region around the city of Shkodër (adjoining Montenegro), and the Orthodox were scattered throughout the towns and villages near the present-day Greek-Albanian border. Before the Communist period there were 30 teqet in Albania, but most of those outside Tirana are still closed. Bektashism is said to have been introduced to Albania from the island of Corfu by dervish Sari Sallteku in the late fifteenth century. He founded seven tekkes, (the Albanian term is teqe) including one on the mountains above Krujë, where he was said to have slain a dragon. The sect increased steadily throughout the country, except in the Catholic areas (to the North). Mehmet II's suppression may not have been unconnected with the fact that Ali Pasha Tepelenë, war-lord of Epirus (much of which has since been swallowed up by Greece), had become a convert.

Many early leaders of Albanian nationalism were Bektashi, and the Order formed the 'left' end of the Islamic spectrum in the Balkans. Following the destruction of the Janissary Corps and the banning of the tariqat in 1826, many Bektashi babas and dervishes fled to the remote areas of the Balkans far from the reach of the Ottoman government. During this period (especially after the order outlawing of the Bektashis was rescinded in the 1860s), the tariqat had gained a sizeable presence in southern Albania. Their toleration and ability to absorb local custom provided the population with a 'folk' Islam that they could easily relate to - and this allowed Bektashism to spread throughout Greece and modern Macedonia - until Greece's ethno-linguistic-religious cleansing policies abolished it together with Albanian language and culture (which had once spread as far south as Athens). Likewise, the Kizilbas (qizilbash) now of Bulgaria (who are the progeny of extremist Shi'a Turkoman tribes who were deported from Anatolia and settled in Bulgaria by the Ottomans following their conflicts with the Safavids) quickly and easily assimilated many Bektashi saints and practices into their own religious doctrines. However, in other areas of the Balkans, such as Bosnia-Hercegovina and in large urban centers (in both where their functioning was limited due the strength of the orthodox Sunni establishment), the Bektashi found restricted appeal and were limited in operation to the Janissary garrisons. These tekkes were established as a result of the Ottoman military presence and disappeared as that crumbled. Several of the more renowned tekkes were found in Budapest (where the tomb of its founder, Gül Baba, still remains and is open for visitation), Eger [now Cheb in the Czech Republic), the building of which still stands), Belgrade and Banja Luka (both of which ceased to exist long ago). In 1922 an assembly of delegates from the tekkes (teqet in Albanian) of Albania severed connection with the Supreme Bektash (himself Albanian, as were so many luminaries and engineers in the Ottoman Empire) who had moved from Istanbul to the new capital of Ankara before the suppression of the order by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Tirana became the sect's seat, and in 1929 it was recognised as an autonomous Muslim order, with new statutes drawn up at Korçë. There was substantial Bektashi influence on King Zog before Albania's annexation by Mussolini in 1938. Under Hoxha (whose name ironically means imam or priest - as Zog's means bird) Bektashis were persecuted and most babas were forced to become agricultural labourers. There is now a large community of Albanian Bektashis in Detroit, [founded by the distinguished Gjirocastrian Baba Rexheb (1901-95) who fled Albania in 1944] which is helping to rebuild the teqet in Albania. For non-Muslims

it is worth explaining that a hoxha or imam is the man in charge

of a mosque. Next in the hierarchy is a Mufti (myfti), and finally

a Khalif. A hoxha can only become a baba if he is

unmarried and if he becomes a murshid through the required communal

and private instruction, and is elected the head of the teqe

or (like Baba Rexheb) founds his own teqe. Another

remarkable Albanian phenomenon is the tradition of THE

BEKTASHI AND TURKISH IDENTITY The Bektashis themselves estimate their numbers at about seven million. Ali Turabi Baba, postnisin of the Bektashi tekke on Mount Tomori in Albania writing in his Historija e Bektashinjvet says that before the destruction of the Janissaries in 1826 and the accompanying abolition of the Bektashi Order, annual statistics were kept, and that these figures showed the number Bektashis to be 7,370,000 - seven million being in Anatolia, 100,000 in Albania, 120,000 in Stambul and the remainder scattered through Irak, Crete, Macedonia and other sections especially of the Balkans. Perhaps the most important justification, however, for studying the Bektashi Order is the fact, generally recognised by all students of Turkish culture to-day, that all down through Ottoman history, when the orthodox religious life of the people was under dominant Arabic influence, when the classic literature in vogue in palace circles was Persian, and when even a great mystic order such as the Mevlevis ['Whirling Dervishes'] based its belief and practice on a book written entirely in Persian, the Bektashis consistently held to the Turkish language and perpetuated in their belief and practice some at least of the pre-Islamic elements of Turkish culture. A Turkish investigator in 1926, writing in the official magazine of the national culture society, makes the claim that the Turkish national ideal never was able to find its expression in the Arab internationalism, but did find it in the tekkes or lodges of the Alevi orders of which the Bektashis and village groups related to them are chief examples. In the secret practices of those religious groups alone was 'national freedom' to be found. The very aim, he says, of the founders of these groups, was to preserve the Turkish tongue and race and blood. That this point of view, while extreme, is not that of an isolated individual is shown by the fact that in 1930 the Department of the Turkish Republic printed 3,000 copies of a book called Bektashi Poets containing biographical sketches and selections from the religious verse of 180 Bektashi poets. In recent years every history of Turkish literature written from school use has emphasized for each century Bektashi Literature because in that, more than in any other type of writing, the original Turkish language and Turkish literary forms were used and Turkish national customs and points of view reflected...

For

fourteen-thousand years I have been in love - [the

town of Sarandë in SW Albania DIFFERENCES

BETWEEN BEKTASHISM AND ISLAMIC ORTHODOXY The religion bestowed by Mohamed very quickly developed in two directions. On the one hand it produced a rigid, scholastic theology with an inflexible religious law ruling the whole society - such as we see today in the Arabian peninsula. At the same time there was the opposite tendency toward a more visionary attitude, developed by individuals and groups who (influenced from the East) emphasized the ascetic life and the mystical approach to direct knowledge of God/Reality. Orthodox Islam is, of course, monotheistic: there is no God but God and Mohamed is His Prophet. But Shi'ites (and Bektashis especially, clashing from their beginning with official Islam) established a kind of trinity of Allah, Supreme Being, with Mohamed and Ali. The son-in-law of the Prophet, Ali, was of course one of the first Muslims and the one to whom Shiites attribute the revelation of mystic understanding of the Koran (Qur'an). Bektashis put Ali, venerated as a saint, only slightly below (or even equal with) Mohamed. This may or may not have been partly a result of Christian influence. Sufism is a philosophical offshoot from Shi'a, in the tradition of Diogenes and other early Greek philosophers - influenced of course from the East. Underlying the various Sufi (philsophical) groups is a recognition that orthodox Islam is essentially an authoritarian patriarchal morality for the mindless. Sufis try to square the circle and make Islam mindful, eclectic, profound and subtle - often by turning conventional Islamic teaching and thought upside down in the manner of revolutionary Zen. Thus many Sufis refer to themselves as 'dogs' (as did Diogenes of Sinope) because of the perceived 'impurity' (and horrible treatment) of dogs by most other Muslims. Other 'impure' animals to Muslims and Jews are rats and pigs. All three are creatures of hygiene: eaters of shit. So are many other animals, especially fish, which are not perceived as polluted. The Bektashis (the most heterodox of Shi'a sects and distinctly antinomian) ignore most conventional Islamic rules, such as abstention from alcohol and pork, the veiling of women and the requirement to face Mecca when praying. They believe that the supreme being is the Divine Spirit of goodness, the life and soul of everything, which manifests itself at different times through different individuals, so that Jesus is revered by Bektashis as a Vessel of the Divine Spirit. One

of the central features of Bektashism, echoing the Athenian Philosophical

model, is the spiritual unit of Master and Disciple. The master/teacher

is known as a murshid, and the disciple or postulant as

a talib (disciple.) A Baba is the man (or, conceivably,

woman) who heads the tekke, like an abbot or prior.

Every murshid

has, of course, been a talib. The intensity of this relationship

is illustrated by a story about a pre-Bektashi Sufi mystic, the

celebrated poet Jalaluddin Rumi

of Balkh (now in Afghanistan) who wrote rhapsodically of his love

for his murshid (whose name, incidentally, means Sun

and came from a previously-Zoroastrian region):- Among Bektashis much importance is also attached to muhabet: verbal communion and chanting or reading nefes, the Bektashi spiritual hymns and poems. In nefes, this 'breath of spirit', the feelings and devotion toward one's particular murshid are endlessly evoked and elaborated. The Bektashis see the power of a nefes as an actualisation of the relationship with the murshid. Verbal and poetic interaction is highly valued among Bektashis - and among Albanians and other peoples temporarily uncorrupted by modern fear of real communication. In Anatolia there was a widespread tendency towards communal life in a brotherhood of those seeking a direct knowledge of God. In general, the ideology of such groups came from Arabic and Persian (and Eastern) sources, the more learned among the Dervish teachers being well able to read and to write in these languages. The most important immediate sources of ideas for all the dervish orders have been the Mesnevi, a great poem written in Persian in the thirteenth century by Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi (the disciple of Shams-i-Tabriz mentioned above), who is the 'patron saint' of the Mevlevi dervish order - and two Arabic works Futuhatý Mekkiye and Fususul Hikâm by Muhyiddini Arabi (1165-1240). Certain orders, of which the Mevlevis ("Whirling Dervishes") are the outstanding example, grew up chiefly in urban centres, as aristocratic, intellectual fraternities, especially attracting members from the upper classes on grounds largely of æsthetic appeal. Other groups, of which the Bektashis are the notable example, arose from commoner concerns. Bektashis, remarkably - like early Christians - considered men and women to be equal, the most chaste being closest to perfection. They accepted and initiated women as inner members since the beginning of the Order in central Anatolia. Their refusal to preach dominion over women brought them criticism from the rest of Islam over the centuries - and yet they never wavered. Women are of course talibs and murshids in the Albanian Bektashi tekke of Detroit - but the number of women in Albanian Lodges before World War II is not known. As mentioned above, Bektashism essentially responded to a need for a religious experience without the ultimately-catastrophic separation between the human and the divine - and indeed between man and Nature - such as exists in the orthodox Sunni (and Jewish) dogma. It responds to the universal yearning for a 'pantheistic' approach and a comforting faith: religion of the heart rather than the book; religion of collectivity; religion of miracle-working saints. In this respect it parallels Greek Orthodox 'Christianity'. The other central feature of Bektashism is an emphasis on progressive initiation into secret mysteries - like the Gnostic Christian sects. Bektashis have also taken over elements of animism, finding God on mountain-tops, in streams and in caves. The teachings of the babas emphasise tolerance, humility, simplicity and practical kindness. Being a Sufi Order, there is a direct philosophical link back to the anti-hypocritical, anti-property, anti-familial Diogenes ("The Dog") from Sinope. Bektashis

also believe that charisma, or divine grace, touches them without

the help of any intermediary, and is in no way affected by any

ritual performed by mediating priests, hoxhas or imams.

Insight being more important than dogma, life for a Bektashi is

a personal induction into wisdom through teaching and communion,

rather than a distant relationship with some supernal grace-dispensing

agency. In this they resemble both the more thoughtful of the

Christian Pentecostals, and the more challenging Buddhist sects.

Turkey's "national poet", Yunus Emre (1240-1321), a contemporary of Haji Bektash, is considered Bektashi, with lines such as A Moses may lie under every stone. One of his poems well-describes the future Bektashi Order of Dervishes:-

Different from

the seventy-two Islamic sects. Whether at the

Ka'aba, in the mosque, Which religious

sect is true, no one in truth can say. Yunus, renew

your soul, be remembered as a Friend of Love, Further Reading:

related

pages: Omar Khayyám of Nishapúr The

Rubaiyát of Omar Khayyám

Albanian

Bektashis in America (with photos) |

|

The

Twelve Pillars or Columns mentioned by Orhan Pamuk are named

in remembrance of Twelve Imams.

2. The Cook, called after Said Ali Balkhi or Seyit Ali Sultan, one of the caliphs of the Order. 3. The Breadmaker, called after Bahim (Balým) Sultan. 4. The naqib (Deputy Shaikh or Registrar), named after Gai Gusus (Kaygusuz). 5. The Keeper of the maidan, who represents Sari Ismail (Sarý �smail). 6. The Keeper of the Cellars, called after Kuli Achik Hajim Sultan (Kolu Açýk Hacým Sultan, �ahkulu Hacim Sultan). 7. The Coffee-maker, representing Shazili (�azeli) Sultan. 8. The Keeper of the Tomb, called after Kara Daulat Jan Baba (Karadonlu Can Baba). 9. The Sacrificer, named after Ibrahim Khalil-Ullah, or the Prophet Abraham of the Old Testament. 10. The Keeper of the Shoes, called after Abdal Musa Sultan. 11. The Groom, named after Qambar (Kamber), the groom of the Caliph Ali. 12. The mihmandar, or the officer charged with attending upon the guests of the takia, called after Khizr (Hýzýr). |

related pages: Omar Khayyám of Nishapúr

and Balkh

The

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

Diogenes of Sinope

The Maxims of Swami Vrkha Baba

A modern Indian Dervish

ATATÜRK

AND THE BEKTASHI FATHERS

A NEO-BEKTASHI POEM

by Anthony Weir

inspired by Boris Poplavski and Omar Khayyám

We saints reject immortality

We don't want blessedness

We ignore fear and desire

We starve our sorrow

We despise prizes and punishment

For we and all are as beautiful

as rats in a sewer

and as irredeemably perfect

as shit.

click here to read versions by Anthony Weir

of

Sufi poems by Jalaluddin Rumi

"Haji

Bektash Veli said:-

There are five kinds of people:

Gentle men who give but don't eat;

Generous men who eat and give;

Mean men who eat and don't give;

Hungry men who can neither give nor eat;

Terrible, ambitious men who eat and do not give

- and work to stop others from giving."

Abu Yi'zza - a black Sufi saint >

Read about a film on the "sworn virgins" of Northern Albania