SATAN IN THE GROIN

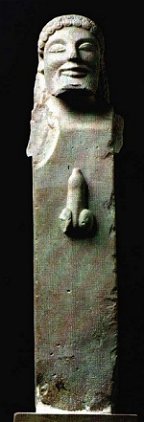

exhibitionist

carvings

on

mediæval churches

DESIRE LARGE AS HELL:

female

exhibitionists:

the

sheela-na-gig conundrum

HIGH-RESOLUTION PHOTOGRAPHS OF MALE AND FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS

beard-pullers

in the silent orgy

ireland

& the phallic continuum

field

guide

to megalithic ireland

the

earth-mother's

lamentation

beasts and monsters of the mediæval bestiaries

Click

to see the carved front of a Romanesque church in Saintonge

(Western France)

FURTHER READING:

Jones, Malcolm

THE SECRET MIDDLE

AGES: discovering the real medieval world

Stroud,

England:

Sutton Publishing, 2002

(especially

the chapter entitled Wicked Willies with Wings: sex and sexuality

in late medieval art and thought).

It

may be ordered

at a discount through:

and outside

the British Isles through amazon.com

AND

Cooke, Ian McNeil

"SAINT PRIAPUS"

an account

of phallic survivals within the Christian church and some of their pagan

origins.

Penzance,

England:

Men-an-Tol

Studio, 2002

(available only from the author)

PLUS

MARGINAL SCULPTURE

IN MEDIEVAL FRANCE:

towards the deciphering of an enigmatic pictorial language

Aldershot,

Hants., England:

Scolar Press.

Brookfield, Vermont, USA: Ashgate Publishing Co.

1995

ISBN 1-85928-109-5

It

may be ordered

at a discount through:

and outside

the British Isles through amazon.com

This book, however, regards subjects such as exhibitionists and mouth-pullers as marginal - which, being on several doorways and interior capitals, they surely are not.

Part of the scanned text is included in the

|

male figures: part III

|

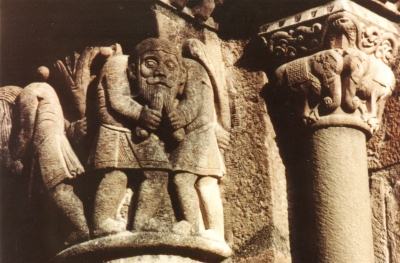

Elines (Santander), Spain

A remarkable variation

on bicorporeality can be seen on a corbel at Saint-Médard-de-Guizières

(Gironde)

where two adossed men share a single penis.

|

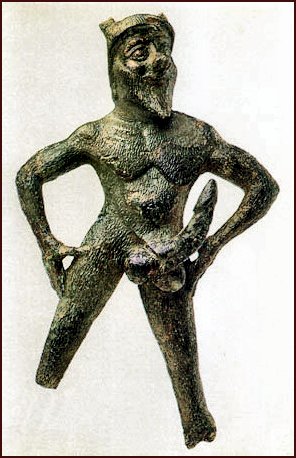

Slightly earlier than the Anglo-Saxon manuscript, the Irish Book of Kells shows a warrior with spear displaying his virility - but as a vignette, without any evident censure. |

|

verse 11: For the stone shall cry out of the wall, and the beam out of the timber shall answer it. verse 11: Woe to him that buildeth a town with blood, and stablisheth a city by iniquity. verse 15: Woe unto him that giveth his neighbour drink, that puttest thy bottle to him, and makest him drunken also, that thou mayest look on their nakedness. verse 16: Thou art filled with shame for glory, drink thou also, and let thy foreskin be uncovered: the cup of the Lord's right hand shall be turned unto thee, and shameful spewing shall be on thy glory... verse 18: What profiteth the graven image that the maker thereof hath graven it; the molten image, and the teacher of lies, that the maker of his work trusteth therein, to make dumb idols ? verse 19: Woe unto him that saith to the wood, Awake; to the dumb stone, Arise, it shall teach...

|

Serious and justified worries about the loose morals of the

rich account for the scenes of lasciviousness and concupiscence

amongst other sins on capitals and tympana. Modern minds, however,

find it difficult to understand why the highly-exaggerated corbel-carvings

were put up on churches - pieces of sculpture sometimes far

more graphic than was doctrinally necessary. A likely

explanation,

less fanciful than it might seem at first, and able to account

for both the Romanesque and most post-Romanesque corbel-figures,

is an anthropological one. The carving of an exhibitionist (male

or female) or any daring or dodgy motif on a corbel-table might

well have been the culmination of the apprenticeship of a sculptor,

literally a licence granted to him by his fellow-sculptors who

certainly were the inspiration of the Freemasons in their confraternity.

Masons' marks occur on churches all over Europe, and especially

in Spain where monks and clerics trailed in the wake of the

bloody Christian war-lord land-grab sanitised under the name

Reconquistà, and built churches with the guilt-money

given them by knightly versions of Milosević and Karadzić

- and Franco.

Even today, masons and sculptors form exclusive tecams and (like many co-operative tradesmen who feel undervalued) perform scabrous rites. In Romanesque times, to be a sculptor was as prestigious as being an international architect today. It is possible that sculptors were more powerful than priests on the ground, because they could simply take off from a site and find employment elsewhere without difficulty. So the carving at Girona (below) might have a different meaning than that which I advanced earlier in Images of Lust. The bishop may well not be overseeing the sculptors like some kind of art commissar, but merely skulking. The sculptors or masons take prominence in the scene, which might be telling us not that nothing went up on a church without ecclesiastical approval, but that what was sculpted went up on a church despite ecclesiastical qualms.

So, in this theory, sculptors who met with the artistic approval of their fellows, had the privilege of carving one or more startling corbel - a kind of satire on the exhibition-piece which is required of skilled craftsmen in wood and stone even today, which then was either slipped past ecclesiastical approval or was placed defiantly or by right and rite. Some (very few) might have had to be placed very high or out of sight to avoid local trouble. But it is pertinent to this theory that many churches in Spain were not properly finished: unfilled scaffolding-holes abound, so teams of masons could up and off with an impunity very similar to the propensity for strike action enjoyed by trades unionists in post-War France and Britain.

The drawback of the theory of initiation-, prentice- or master-pieces of sculptors fully received into their teams, guilds or confraternities is that a few of the Romanesque males are extremely crude efforts. These exceptions might well be simple imitations on churches whose sculptors were not master-craftsmen..

Cloister capital, Girona (Spain) click to enlarge

However,

some extremely well-carved male

exhibitionist gargoyles

and other figures can now be seen high up on church towers,

out of sight except to the keenest eyes (which were not so common

in mediæval times) - for example Ewerby

(Lincolnshire) and Wiggenhall

(Norfolk) - and even on secular buildings, as at Bruniquel

(all mentioned above). The beam-carving at Claybrooke

Parva is tucked away high above the western end of the nave

and is quite small to the unaided eye. Without modern binoculars

and a powerful torch it would be easy to overlook.

Male exhibitionists are not magical. Nor are they simply ancient survivals from an imagined, invented "Celtic" or Classical-pagan past, but sculptures which fitted into their Christian context by dint of - on the one hand - widespread and uncontrollable concupiscence amongst the peasantry and to an extent amongs the lowliest clergy who were drawn from that peasantry. On the other hand, they might very well have been not only exhibitionists but exhibition pieces, proudly and lewdly displayed by master-craftsmen as quasi-pious jeux d'esprit.

|

Orpheus as Adam, Lord of the Beasts in Eden on a 5th century ivory in the Bargello Museum, Florence. |

In the same spirit of joie-de-vivre -in opposition to the Christian use of the exhibitionist motif - is a remarkable pair of gateposts in county Donegal in north-west Ireland. These are covered by cement rendering, into which were incised - when wet, sometime near the end of the twentieth century - a male and a female exhibitionist figure facing each other.

click to read about this syncretic piece of 'folk-art'

Anti-copyright Anthony Weir, 2007-2012

|

Compare this late 14th century anal exhibitionist from the

Gorleston Psalter.

This is a direct (if anatomically incorrect) lampoon on sexual

practices in monasteries.

The brown habit is worn by the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor

and Friars Minor Capuchin.

An antique (probably Roman) brothel-token.

ESSENTIAL READING

FURTHER READING

Sodomy,

Masculinity and Law in Medieval Literature: France and England,

1050-1230

(Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature)

by William E. Burgwinkle, 2009.

The Introduction

and Conclusion can be read online.

Here are a few lines from the Conclusion.

"St

Anselm defended his reluctance to prosecute sodomy in 1102 with

the argument that it was already so commonly practised that

people would have difficulty recognising it or themselves within

the category. Such a statement could not have been made by the

end of the century, when 'sodomy' had become a matter of discourse

and persecution. In the intervening years, increased attention

to celibacy, monastic rules, marriage practices, and the status

of knighthood had the effect of calling attention to the performative

nature of masculinity, to its ritualisation and theatricalisation.

Institutions responded by setting up ever more rigorous criteria

by which men earned, or failed to earn, their masculine status;

and accusations of sodomy began to feature in these attempts

to discipline masculine subjects by controlling and patrolling

gender barriers.."

| The Enigma of the 'Sheela-na-gigs' |

The MYSTERIES of the COLUMN-SWALLOWERS >

The

pictures and text on these pages are condensed from a former Work in

Progress, The Silent Orgy.

They are dedicated

to the late Martha Weir,

who was amazed but unfazed by these carvings,

and without whom Images

of Lust"

would never have been researched or written.

|

Click

here for a related essay: |

See also:

and

Another Irish Sheela-na-gig Website >

|

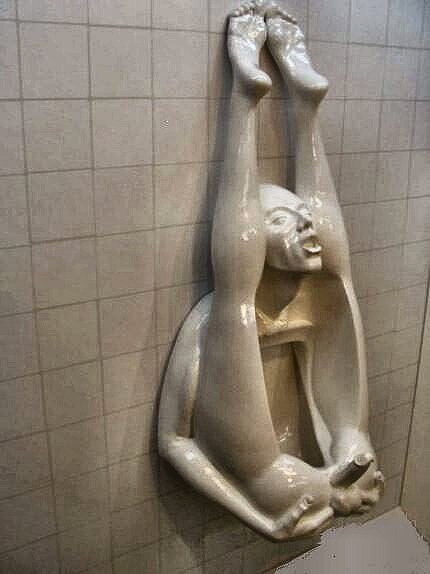

A

very modern interpretation

of the Male Exhibitionist Motif >

|

He

says it is a stonemasons' tradition to do so and said that anyone

looking for it would have to look carefully to find it. Cathedral

spokesman Glyn Morgan said they were not too surprised as they

were aware of the craftsman's tradition of leaving little jokey

reminders.

June 2007 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/hereford/worcs/6249344.stm

|

Within the context of images of lechery, this report should be treated with caution.

I am especially grateful to Tina

Negus, Julianna Lees, Jacques

Martin, Kjartan Hauglid, Bob Trubshaw and John Harding

for their generous help and donation of photos to this website.

SEARCH THIS SITE USING

This site has been empowered by FloatBox

another

another