Diligent

Websites

ARTICLE FROM AEON, May 2023

https://aeon.co/essays/from-the-cynics-self-sufficiency-to-an-ecology-of-wanking

M.D.Usher

| In his sixth

Discourse, the orator Dio Chrysostom (c40-120 CE) relates a curious

detail about the Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope (404-323 BCE).

Diogenes, Dio tells us, was particularly fond of the myth about

the god Pan’s discovery of masturbation. By Dio’s time,

Diogenes himself was already famous for the practice, owing to his

public displays. ‘If only it were so easy to relieve hunger

by rubbing one’s stomach,’ he is reported to have said

when confronted about it. ‘When fish need to ejaculate,’

he observed another time, again in self-defence, ‘even they

are more sensible than humans. They just go out and rub themselves

off on something rough.’ But Diogenes’ interest in the

aetiology of masturbation presents us with more than a justification

for an off-colour antic. It is, I would like to suggest, a meaningful

ecological gesture.

Pan, the story goes, frustrated by his fruitless pursuit of the nymph Echo, learned the technique from his father, Hermes, and later taught the trick to shepherds to help them cope with having to spend so much time alone in the mountains. If everyone practised such autonomy, Diogenes argued, the world would be a better place. There would have been no Trojan War for one thing, because philandering Paris would have had no need to abscond with Helen. As Dio summarises Diogenes’ point: That for

which men have given themselves the most trouble and spent the

most money, which has caused the razing of many cities and the

pitiful destruction of many nations, is really the least laborious

and most inexpensive of all things to procure. The Cynic quest for autarky, despite what it may seem, is a call to freedom through conformity – freedom from the injurious conventions of society by means of conformity with conditions found in nature. The problem with Homo sapiens sapiens, according to Diogenes and his followers, lies in a fundamental confusion of needs and wants. We have become dependent, the Cynics argued, on unnecessary luxuries that have made us physically soft and morally weak. We are not satisfied with having our needs met but go to costly, harmful lengths in search of pleasure and novelty. Nonhuman animals, by contrast, live happily within the compass of their means – the environments that nature has provided for them. They understand their place in the world and accept it. In response to this realisation, the Cynics conducted a lifestyle experiment to see how much of human society they could do without. They lived outdoors and scrounged food, or foraged, and begged. They preferred to drink water than wine – a gift of nature versus a commodity of culture – and were content with that. Asked what kind of wine he did like to drink, Diogenes replied: ‘Somebody else’s.’ Asked at what hour one should eat lunch, he said: ‘If rich, whenever you want; if poor, whenever you can.’ You can drink wine, in other words, when it is provided by others, but you have no need for it; you eat when there is food, but if there is none you can go a spell without it. The Cynics were not the world’s first ascetics, to be sure, but they have given us that word – from Greek askesis, which literally means ‘practice’ or ‘training’. The metaphor is drawn from the realm of ancient Greek athletics. Getting by on just a little is a form of exercise, the Cynics argued, that will strengthen you and make you impervious to the buffetings of misfortune. And yet the Cynics’ philosophy of ‘less is more’ and of ‘put up and make do’ was also a form of self-actualisation. ‘It is the gods’ prerogative to need nothing,’ Diogenes liked to say, ‘but for the god-like to need only a little.’ Their perverse style of reasoning along these same lines produced mock syllogisms like this: Everything

belongs to the gods.

Even

the despising of pleasure is itself most pleasant once it’s

become a habit … Just as those who’ve gotten accustomed

to a pleasant life become miserable when they pass over to the

opposite condition, so those persons whose training has been the

opposite from theirs enjoy despising pleasures with more pleasure

than the pleasures themselves.

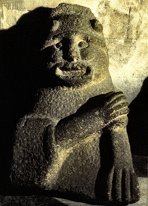

By watching a mouse scurrying about – not anxious for a place to sleep, not afraid of the dark, nor pining away for any of the so-called pleasures – he discovered a way to cope with his surroundings. People are animals, too, of course. With their appeal to the natures of nonhuman creatures, the Cynics invite us to consider how the human animal should be interacting with its Umwelt – how, in other words, we might live ecologically, given the morphology and sensory receptors we possess. One ancient admirer calls attention to one of Diogenes’ favourite refrains: ‘With respect to living life one must either use one’s noggin or a noose.’ Human animals possess the capacity to make reasoned decisions and choices. It is within our power, the Cynics want to show us, to control and channel our appetites, to live according to our nature. While the Cynics were not perfect rationalists (how, for example, can begging be squared with self-sufficiency?) they believed that reason defines, and so must inform, our species’ interactions with its Umwelt, lest we make life itself unliveable. Diogenes and company, like the performance artists they were, took their shtick to an extreme by acting out in purposefully antisocial ways to underscore their points – showing as well as saying. For this they were called dogs by their detractors, which is how we get the word ‘Cynic’ from ancient Greek. Anyone who has visited modern Athens will have seen the city’s ownerless dogs roaming the streets, pawing through bins, and lounging in the sun amid the dilapidated remains of high civilisation. That is exactly how we are to imagine the ancient Athenians picturing Diogenes. With typical self-effacing irony, Diogenes embraced the moniker, casting himself as the city’s moral watchdog, barking truth from the sidewalks and nipping at the heels of rogues. He even lifted his leg and pissed on some hooligans teasing him in the street, shouting ‘dog’ at him. Dogs, of course, do not have opposable thumbs. But humans do. Masturbation, the Cynic solution to avoiding the interpersonal and social harm often caused by sexual urges, thus deploys an evolutionary advantage adapted to the human species to address an evolutionary phenomenon that besets the human animal – an obsession with sexual gratification apart from its use for procreation. This, the Cynics argue, is where trouble often arises. They were not alone in thinking this way. In an entertaining dialogue called ‘The Oinker’, Plutarch (c45-120 CE), who was not a Cynic, puts on the lips of one of Odysseus’ men whom the enchantress Circe has turned into a pig the following arguments in defence of animal virtue: Our females are not coy and do not hold forth with deceptions, sweet-talk or refusals. Our males aren’t driven mad with lust. Animals don’t purchase the work of procreation with payments, labour or servitude. Rather, both parties come together in a sexual union that is without guile and free of charge, which awakens our desire in the season of spring, like the blossoming of plants, whereafter it is immediately quenched: the female does not receive her mate after she has conceived; nor does the male attempt to mount her. That’s how weak and small we think pleasure is. Nature, rather, is our whole concern.One can admire the Cynics for their tenacity and integrity, if not for their logical consistency. They were, above all, terrific entertainers in their time. But domesticate them a bit and the dog philosophers’ core ideas have surprising traction today. A lot can issue from an ecology of wanking. Here are a few examples. To their credit, the Cynics’ radical perspective on self-sufficiency is suffused with a concern for the self-sufficiency of others. The Cynics well understood what economists now call ‘externalities’, or the harmful side-effects and human/environmental costs involved in the production and acquisition of goods. In a dialogue attributed to the satirist Lucian of Samosata, an unnamed Cynic likens the god in charge of this world to ‘a good host’ at a dinner party: He places

before us a variety of many kinds of dishes so that we have what

is appropriate for us – some things for the healthy, some

for the sick, some for the strong, some for the weak – not

so that we all may use everything, but so that each of us might

use for ourselves what falls in our domain and, of those items,

what we happen to need most. 'are exactly like a person who grabs everything out of greed and lack of restraint. You think it’s fine to use it all, including goods from all over and not just what you have close to hand. You don’t think your own land and sea are enough in themselves, but import your pleasures from the corners of the globe and always prefer what is foreign to what is produced locally, what is costly to what is inexpensive, and what’s hard to procure to what’s easily acquired … The many costly goods you think conducive to your happiness, over which you exult, only come to be yours through misery and suffering. That gold you pray so hard to get your hands on, the silver, the expensive houses, the finely tailored clothing, and all the accoutrements that go along with these things: how much do they cost in trouble? How much in human labour and danger, or rather, in human blood, death and destruction? Many people are lost at sea for the sake of such things, and the people who go in search for or manufacture them suffer terribly.' The recognition of externalised costs and the preference for local goods and services over imported products enlarges on the meaning of cosmopolitanism, another word and concept the Cynics invented: the consequences of our choices – and thus our obligations to our environments and to one another – extend far and wide, and in many directions. We are inescapably ‘citizens of the world’ and must behave as such. Did someone say decluttering and detachment? Marie Kondo has nothing on the Cynics. The concept of ‘appropriate technology’ was developed by E F Schumacher, the author of Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered (1973). The idea came to him in the 1950s and ’60s while he was working as chief economist for the British National Coal Board and as a consultant to former British colonies in South Asia. Schumacher was heavily influenced by Gandhi, whose All-India Spinners’ Association sought to establish India’s economic independence from Britain via self-sufficient, small-scale, local production and consumption of goods, symbolised by traditional homespun cloth. Schumacher himself used the term ‘intermediate technology’, by which he meant a technology superior to inefficient, rudimentary tools and practices, yet one ‘simpler, cheaper and freer than the supertechnology of the rich’. The thrust of the idea is never to use more than you need, of either labour or materials, to get a job done, and thereby eliminate both waste and unnecessary expense. Diogenes seems to have anticipated him in this. As one ancient biographer describes his revelation: Once, after observing a child drink water from his hands, Diogenes [is alleged to have] hurled his cup from his knapsack, saying: ‘A child has vanquished me in simplicity!’ He tossed out his bowl, too, when he saw in like manner a child who had broken his plate take his lentils in a hollowed-out hunk of bread. That’s quite a statement, as Diogenes was a man of only a few possessions to begin with. He is popularly remembered as having lived in a tub or barrel. One sunny day, Alexander the Great is said to have paid poor Diogenes a visit, offering to grant him any wish he might make. ‘Stand aside, please,’ was Diogenes’ request, ‘out of my sunshine.’ In fact, Diogenes’ abode was a pithos (large terracotta storage jar), which he had repurposed as his house. Given that pithoi were frequently used to bury the dead, like a coffin, this choice of accommodation not only advertised Diogenes’ frugality and resourcefulness, it was also a statement of the philosophical view that life is a rehearsal for death. Did someone say decluttering and detachment? Marie Kondo has nothing on the Cynics. In our age of wasteful, unneeded, energy-consuming gadgets, appropriate technology is the ticket out. Appropriate or not, technology can only get you so far. As Garrett Hardin argued in his essay ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ (1968), problems involving common-pool resources like land, air, fresh water and the oceans are not caused by technology, and thus are not amenable to technological solutions. We tend to blame trains, planes and automobiles for our climate predicament. But it’s really misplaced human wants, desires and errors in judgment that are the sources of our catastrophe. The year 2022 marked the 50th anniversary of the book The Limits to Growth. That landmark indictment of human overreach and excess, first published in 1972, is a bible of the environmental movement. In our new climatic regime of global heating, it remains scripture, even if not infallible on the finer detail. The book’s authors – Donella Meadows and her fellow researchers at MIT via the Club of Rome – used systems modelling to demonstrate that, while rates of increase in the world’s population, pollution levels and depletion of natural resources are fundamentally exponential in nature because of reinforcing feedback loops, our technological capacity to remediate these problems is confined to a linear trajectory. To put it another way: we will never catch up. We must, therefore, slow down. The Cynics have something to teach us here, too. They are the gurus of degrowth. Masturbation, it will be observed, in an age before contraception, also serves as a check on the human population. Hardin urged us to curb human procreation on a sociopolitical scale democratically, by exercising ‘mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon by the majority of people affected.’ In a world of finite resources and free markets, he argued, the freedom to breed will eventually make conditions conducive to human freedom impossible. To the contrary, he insisted, quoting G W F Hegel (actually, it was Friedrich Engels who said it): ‘Freedom is the recognition of necessity.’ The argument has a certain Cynic ring to it, though the Cynics themselves were admittedly more misanthropic on the matter: ‘Whoever follows us will remain single,’ was Diogenes’s ultimatum. ‘Those who do not follow us,’ he conceded, ‘will rear children. And yet, if the human species should become extinct,’ he adds, ‘there would be as much cause for regret as there would be at the annihilation of wasps or flies.’ From the vantage point of the biosphere (and with apologies to wasps and flies, which are as essential to biological diversity as we are not), this is undeniably true, the so-called Anthropocene be damned. A post-human world seems one the Cynics can imagine and accept. Humans are social as well as sexual animals, and the two aspects are not unrelated Some Cynics did marry. To watch the Cynic power-couple Crates and Hipparchia perform their conjugal duties in the streets of Thebes proved quite an attraction to passersby. Theirs is a love story for the dogs. Despite an aristocratic upbringing, Hipparchia followed, then fell in love with, Diogenes’ disciple Crates of Thebes (c365-285 BCE), married him, and the two pursued the Cynic life together. The Stoic Epictetus (c50-135 CE) opined that their Cynic coupling was the exception that only proves Diogenes’ rule since, he suggests, Crates and Hipparchia had merely found their autonomous spiritual selves in one another. A pseudepigraphic epistle imagines the birth of their child and how they might raise him: ‘Let his bath water be cold,’ Crates advises Hipparchia with a bit of mansplaining, ‘and his food be milk – just enough, not to excess.’ Scaling up a notch of relational complexity, Diogenes’ nemesis Plato (427-347 BCE) was certainly more realistic to assert in his Republic that ‘a city comes to be because none of us is self-sufficient.’ Self-sufficiency has its limits. Humans are social as well as sexual animals, and the two aspects are not unrelated. ‘Could it be,’ Plato speculates, ‘that justice itself resides in some need that people have of one another?’ Yet even in Plato’s ideal primitive community, what one detractor in the Republic calls ‘a city for pigs’ for its lack of gourmet cuisine, the citizenry is noted for its earthy temperance and restraint: They’ll feast on barley meal that they’ve prepared for themselves, and wheat, baking some of it and mashing some into excellent loaves and cakes. This they’ll spread out to eat on any old patch of reeds or clean leaves. Reclining on beds woven out of bryony and myrtle boughs, they and their children will feast sumptuously, then sip wine, hymning the gods. They will enjoy sex with one another, yet not produce children beyond their means, thus on their guards against poverty, or war … And living life in this manner in peace and with good health they will reach old age and pass on to their progeny a life just like the one they themselves enjoyed. If that is not the spitting image of sustainable, ecological living, I do not know what is. As for the Cynics, they are best regarded not as paragons of what is practicable, or even reasonable, but as mascots or effigies of what is humanly possible. In antiquity, no Hellenistic city lacked its resident Cynic, and the Cynic way of life enjoyed considerable longevity, lasting nearly 800 years before transubstantiating into Christian monasticism. St Francis of Assisi (c.1181-1226) in particular, whom Lynn White, Jr once called ‘the patron saint of ecologists’, looks a whole lot like the Dog from Sinope. The Cynic message persists even though times have changed. And their ecological legacy lives on, too, not only in the likes of Francis, Schumacher, and Hardin (who, incidentally, had four children), but also philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Henry David Thoreau (both life-long bachelors), as well as the Depression-era back-to-the-land couple Scott and Helen Nearing, the Crates and Hipparchia of my native Vermont. M D

Usher is the Lyman-Roberts Professor of Classical Languages and

Literature |