|

a

HOLY DOG

and

a DOG-HEADED SAINT

St Guinefort and St Christopher Cynephoros or Cynocephalus

Anthony Weir

detail of Ikon painted by Artëm Kotyenko, 2000

|

The legend

of Saint Guinefort concerns

a greyhound said to have lived in mid-13th century France. Dogs

in feudal (as in Celtic) times were often highly-prized - especially

hunting-dogs. They were also a source of warmth on the baronial

bed during cold nights in unheated, cavernous and draughty stone

castles.

Guinefort, a trusted family member, was, as often happened, left

to guard an anonymous (but certainly seigneurial and almost certainly

male) infant. When the father returned he saw blood covering the

room and surrounding the infant's crib. Guinefort sat next to the

crib, with blood around his mouth. Immediately the man took his

bow and shot the dog in the heart. As the infant cried out, he realized

his tragic error, and, on approaching the crib, he saw that his

child was unharmed. Below the crib was the body of a dead snake

(Satan ?) who had been creeping up on the infant. Guinefort had

saved the child's life - and possibly his eternal life. In his grief,

the father committed the dog's body to a well and (in the ancient

Celtic tradition) planted a grove of trees around it to honour the

brave greyhound. Local peasants and villagers, when they learned

the story, began making pilgrimages to the grove to pray to the

canine martyr.

This is the international

folktale (motif B524.1.4.1.) known as The Faithful Hound.

The primary textual traditions of this particular variant - The

Dog-Saint - come from De Adoratione Guinefortis Canis (Concerning

the worship of the dog Guinefort). It somehow came to be attached

to a local Burgundian saint associated with the healing of children,

who thereby was transmogrified into a greyhound.

"This recently happened in the diocese

of Lyons where, when I preached against the reading of oracles,

and was hearing confession, numerous women confessed that they

had taken their children to Saint Guinefort. As I thought that

this was some holy person, I continued with my enquiry and finally

learned that this was actually a greyhound, which had been killed

in the following manner...[T]he peasants, hearing of the dog's

conduct and of how it had been killed, although innocent, and

for a deed for which it might have expected praise, visited the

place, honoured the dog as a martyr, prayed to it when they were

sick or in need of something..."

Étienne

de Bourbon, an inquisitor reporting from Dombes, north of Lyon

(a small area now straddling the railway-line in the département

of the Ain between Lyon and Bourg-en-Bresse), recorded the above

account in his 13th century narrative supporting Guinefort's designation

as a heretic. He had the dog "disinterred, and the sacred

wood cut down and burnt, along with the remains of the dog."

Apparently a dog cannot be an official saint, though he can be

an official heretic. Despite the best efforts of the Inquisition

to eradicate the cult of Saint Guinefort, people continued to

visit the grove up to 1940, praying for the protection of their

children. Ruins of a chapel dedicated to St Guinefort survive

at Trévron in Brittany (Côtes d'Armor). In 1987,

a movie was even made about the dog and his cult (The Sorceress,

France 1988). The 14th century Saint

Roch from Montpellier is also associated with a

dog - who, during the Black Death, stole bread from his master

for the saint when he was a plague-victim starving in the forest.

The saint's history continues, but the dog drops out of the story.

There

is an obvious connection between St Guinefort and St Christopher

who is sometimes called Cynephoros in Greek (dog-faced)

- though more often Cynocephalos (dog-headed). There are

indeed some ikons of him shown with a dog's face. These are highly

illicit - although illicitness and impropriety rarely get too

much in the way of iconographical expression. So the story of

St Guinefort is probably a popular misunderstanding of the cult

of Christopher - Christophorus Cynocephalus or Cynephoros

being easily corrupted to Guinefort. At the very least, it

was strongly influenced by the dog-headedness of Christopher.

The cynocephalic St Christopher

story also seems to have been known in England, though Old English

traditions of the saint are rather unusual. According to the Old

English Passion of St Christopher, he was healf

hundisces mancynnes, 'of the

race of mankind who are half hound'. The Old English Martyrology

elaborates upon this:

...he was thære theode wær men

habbath hunda heafod & of thære eorthan on theare æton

men hi selfe,

'from the nation where men have the head of a dog and from

the country where men devour each other'; furthermore, he

hæfde hundes hæfod, & his loccas wæron ofer

gemet side, & his eagan scinon swa leohte swa morgensteorra,

& his teth wæron swa scearpe swa eofores texas -

'he had the head of a hound, and his locks were extremely

long, and his eyes shone as bright as the morning star, and his

teeth were as sharp as a boar's tusks'.

Dogs

were highly prized in Celtic societies - at least as much as racehorses

in ours - and the Celtic legends and mythologies celebrate various

dogs called Bran. The name of the Irish hero Cú Chuailláin

means Hound of Ulster. A

Cú was

much more valuable than a Madabh (farm dog). The Welsh dog-hero/saint

Gelert, associated with Prince Llywelyn the Great (1173-1240),

is, however, a romantic fiction of the late 18th century derived

from a 5th century Indian Buddhist work, the Pancha Tantra.

The story gained wide currency in Europe in the Middle East. The

heraldic Rous Roll of the 15th century, for example, depicted

the arms of Wales as a helmet on which stand a dog and a cradle.

But it was finally applied specifically by a hotelier to the village

of Beddgelert, named after an obscure, early-mediæval, local

saint. To reinforce the story further, he erected a megalith,

Gelert's Bed. The 'new' story became the subject of a poem

by W.R. Spencer which Joseph Haydn set to music. Such is the stuff

of nationalist legend - and this is one of the more benign examples...

click here for another bogus saint with an even more amazing legend

and origin >

In

the Physiologus, the early-mediæval source of the

late-mediæval Bestiaries, dogs are praised for "having

more understanding than any other beast" - and for knowing

their name and loving their master. Dogs "are like preachers

who by warnings and by righteous living turn aside the ambushes

of the Devil...As the dog's tongue heals a wound by licking, so

the wounds of sin are cleansed by the instruction of the priest

when they are laid bare in confession." There is also

praise for dogs within dog-hating Islam.

The

Physiologus also features Cynocephaloi or dog-headed

humans.

This is a charming 16th century illustration.

Though the myth of

dog-headed people largely derives from the depictions of the Egyptian

Jackal-god, Anubis, of whom toga-clad statues were made in Roman

times, early Greek writers reported dog-headed (shaggy ?) people

living in the Himalaya.

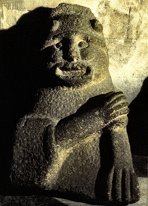

Romanesque

sculptors inevitably co-opted the motif, as in this fine detail

of an archivolt at Vézelay (Yonne).

|

top of  page

page

|

Ikon of St Christopher Cynocephalus,

from the Byzantine Museum of Athens

Ikon from

the Church of St. George,

Çegelköy in ancient Bithynia,Turkey.

Two Russian ikons of St Christopher

(whereabouts unknown to this writer)

I

am indebted to my friend Artëm

Kotyenko of St Petersburg for bringing St Christopher Doghead to

my attention.

|

The Legend of

The Dog-headed

Saint Christopher

David Woods of University

College, Cork, has collected the essential texts in this tradition

at his St.

Christopher website. Here is an excerpt from an Irish

Passion of Saint Christopher:

Now this Christopher was one of

the Dogheads, a race that had the heads of dogs and ate human

flesh. He meditated much on God, but at that time he could speak

only the language of the Dogheads. When he saw how much the Christians

suffered he was indignant and left the city. He began to adore

God and prayed. "Almighty God," he said, "give me the

gift of speech, open my mouth, and make plain thy might that those

who persecute thy people may be converted". An angel of God

came to him and said: "God has heard your prayer."The

angel raised Christopher from the ground, and struck and blew

upon his mouth, and the grace of eloquence was given him as he

had desired.

Thereupon Christopher arose and went into the city, and immediately

began to stop the offering of sacrifice. "I am a Christian,"

he said, "and I will not sacrifice to the gods". There

came a certain Baceus to him and struck him. "You may do so",

said Christopher, "for I will not strike you in return, but

I forgive you, for forgiveness is the new law."

Baceus went to the king, and said: "Hail O King, I have news

for you. I have seen a man with a dog's head on him, and long

hair, and eyes glittering like the morning star in his head, and

his teeth were like the tusks of a wild boar. I struck him for

he was cursing the gods; but he did not strike me, and said it

was for the sake of God that he refrained. I am telling you this

in order to know what is to be done with him, for it seems that

it is by the God of the Christians that he has been sent, to help

the Christians."

"Bring him to me," said

the king. The bystanders said that a large number of men must

be sent for him. "Let two hundred soldiers go for him,"

said the king, "and bring him hither in chains; and if he resist

you, bring his head with you that I may see it."

Read

the rest of St. Christopher's life and martyrdom.

The Origin of the Cult of St. Christopher

(abridged from a text by David Woods)

St. Christopher was a member of the north African tribe of the Marmaritæ.

These inhabited the fringe of the Known World, where, tradition

had it, people were cannibals, sciapods, cyclops, hermaphrodite

or dog-headed. The latter myth derives from the appearance of baboons,

and has nothing to do with the Egyptian cult of Anubis.

Christopher was captured by Roman

forces during the emperor Diocletian's campaign against the Marmaritæ

in late 301/early 302 CE and was transported for service in a Roman

garrison in or near Antioch in Syria. He was baptised by the refugee

bishop Peter of Alexandria and was martyred on the 9th of July 308.

Bishop Peter arranged for the transport of his remains back to Marmarica

in 311. He is really identifiable with the Egyptian martyr known

as St. Menas. Insofar as the author of the lost, original

acts of St. Christopher seems both to have been based at Antioch

and to have wanted to encourage missionary activity, he is probably

identifiable as Bishop Theophilus 'The Indian', present at Antioch

circa 351-54, or as one of his circle. The fact that St.

Christopher was martyred in one place but buried in a far distant

region may explain the unusual development of his cult.

As to to the vexed question of Christopher's

real name, the name Christopher, the same in Greek and Latin, meant

"Christ-Bearer". There is no evidence to support

its usage as a first name at this early date. It was still being

used as an honorific title only, it would seem. According to the

earliest Greek passions, Christopher only took this name at his

baptism, before which he had been known as Reprebus. The

earliest Latin passion reports a similar tale except that they preserve

the name as Rebrebus. Both names look very like corrupt readings

of the Latin term Reprobus meaning "wicked". Hence

these texts seem to tell the tale of a wicked man, i.e. Reprobus,

who became a bearer-of-Christ, i.e. Christopher, and to that extent

they read suspiciously like a moralising tale rather than a factual

report. It is arguable, therefore, that St. Christopher's real name

has been lost. In so far as there exists an inscription commemorating

the dedication of a Church of St. Christopher in Bithynia (south

of the Black Sea) in 452, it is clear that it must have been lost

at a very early date. Indeed, the fact that none of the surviving

versions of the acts of St. Christopher preserve his real name suggests

that this name had already been lost before the author of the lost,

original acts composed his work based on the few surviving facts

that tradition had managed to preserve until that time.

In Russia and Finland

a different story - emanating from Cyprus - accounts for his cynocephaly:

he was so handsome that he attracted the attentions of young girls.

When he was baptised, he prayed to God that he would get such a

face that nobody would be attracted to him. God responded to his

prayers and gave him the face of a dog.

click

to enlarge

Seventeenth-century Russian ikon

of SS Stephen and Christopher.

|

read

more on ikons of St Christopher Doghead...>

click

here

to see a 20th century 'freak',

Stefan Bibrowski, alias Lionel the Dog-faced Man.

top of top of  page

page

an

edited version of

"Holy Dogs and Asses:

Stories Told Through Animal Saints"

by Laura Hobgood-Oster, Ph.D.,Department of Religion and

Philosophy

(Brown Working Papers, Southwestern

University)

Saint Anthony,

the founder of Christian monasticism, thought he was the first

monk to live the solitary life until he heard of Paul the Hermit.

In the third century CE, Paul left human society for the desert

where he lived in a cave for sixty years. Anthony decided to find

the Hermit. As the legend goes, a wolf "came to meet him"

and proceeded to lead him to Paul's cave. The Hermit refused at

first to speak to Anthony, but finally convinced he was genuinely

seeking to be a hermit, the two embraced.

Soon, another animal entered the scene. When they started to become

hungry, a crow flew down, carrying a loaf formed of two halves.

Anthony wondered at this, but Paul told him that God provided

him daily with food: this day the quantity was doubled to take

care of the guest: the crow knew of Anthony's presence and brought

enough food for both of these early Christian saints.

[click

to read about another much-venerated desert saint]

During his time

in the wilderness, Paul's companions had all been animals. They

knew his location, led the wandering Anthony to the Hermit, provided

Paul with nourishment and served as his only companions.

Paul died shortly after the encounter with Anthony. When Anthony

returned and found him dead, he determined to bury him even though

he lacked the means. Animals again came to his service. Two lions

appeared, "dug a grave, and, when the saint was buried, went

back to the forest." This account is one of the rare appearances

of other-than-human animals in the hagiography.

Are these animal epiphanies rare or, rather, rarely noticed ?

A careful probing of the stories of the Christian tradition reveals

more animals than this religion, often classified (alongwith the

other monotheisms) as extremely anthropocentric, would seem likely

to incorporate. This paper seeks to recover a lost strand of silenced

animal voices in the history of Christianities.

After studying many written texts and examining numerous visual

representations, a framework for understanding the inclusion of

animals emerges. Animals appear as saints, as sacraments, as revealers

of the divine, as bearers of God or as Imitatio Christi

imitators of Christ. In these rôles animals act, are

acted upon, and enact the will of the divine. Amazingly ,their

agency and power, their action as subjects in their own right,

is prominent in myriad stories and is central in numerous images.

As the history of Christianity intertwined with that of patriarchal

and imperialistic Mediterranean and European powers, the dominant

forms of Christianity became increasingly anthropocentric. Animals

and their stories ceased to have a significant "voice"

in the Christian "choir."

During and after the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment,

Christianity,

along with the majority of interlocked European cultural systems,

severed ties with the rest of nature. Thus an alienation from

any being other than the human, or the human-like divine, set

into these dominant forms of Christianity.

This intense, dualistic transformation suppressed the holy animals

within the religious tradition and its history.

Whereas the presence of animals had been integral to some aspects

of various forms of Christianity in their earlier manifestations,

the proclamations of such theologians and philosophers as René

Descartes struck the final blow to the efficacy and inclusion

of animals in the circle of religious dialogue. Humans, ascendant

for centuries, began to understand themselves as the only subjects

worthy of divine consideration. All other animals were simply

tools for human use.

Of course, this hierarchical ranking of humans over animals interlocked

by many systems of oppression that travelled with European imperialism

to the rest of the world. The binaries that place male over female,

the European "race" over all "races" of "colour,"

and mind over body, just to name a few, connect directly to the

ranking of humans over all (other) animals. As long as one of

these systems of domination remains, none of them is truly subverted.

Articulating the significant rôle that animals have played

throughout the scope of Christian

history strengthens the process of ending the interlocked dominations.

It also provides one of many perspectives that have the potential

to influence the development of a renewed, biocentric 'Christianity'.

Representation and Animals in Christianity

Distinct cultural patterns and symbol systems shape human experiences

of and relationship to other living beings in our environments.

Patterns are encoded in visual representations (a pig is presented

as a strip of bacon), in language (animals are referred to as

"it" rather than as "he" or "she")

and in daily, pragmatic ritual performances (a homeless animal

is often "put to sleep" and treated as a nuisance).

The societies that have formed around , influenced and been influenced

by Christianity in its European and North American settings have

informed many of these cultural patterns and symbol systems in

profound ways. Animals are regarded as subordinate, irrational,

soul-less beings whose primary purpose is based on a theory of

utilitarianism that places human beings at the top of a hierarchy.

Animals exist for human consumption, labour and æsthetic

or emotional pleasure alone. Intrinsic value and direct relationship

between animals and the sacred is denied.

But has this cultural pattern been static, or has some transformation

of understanding occurred ? Did animals once engage humans and

God, within 'Christianity',

differently? If so, why would it matter or what could it affect

? The thesis that I offer is based on recovering an understanding

of the relationship between humans and animals within the history

of Christian traditions. Do certain patterns suggest cultural

continuities and shared symbols ? Are animals legitimised or denigrated

in the sacred history of this multi-faceted religious tradition

? What developments are linked to changes in these representations

and experiences of human and animal ? What transformations take

place in these relationships and how do these point toward other

historical patterns?

In this paper I will address the first two questions in particular

and suggest possible directions for continued research and analysis.

Christianities grew out of the various religious traditions found

in the Mediterranean world two thousand years ago. Judaism, mystery

religions, myriad pagan traditions and the official religion [was

there one ??? A.W.] of the

Roman Empire, to name just a few, provided the primary sources

for early forms of Christianity. As they develop, Christianities

incorporate various aspects of these traditions and their belief

systems. From this process a rather ambiguous place is forged

fo animals in Christian traditions. Each of these religious traditions

included and excluded animals in various ways, thus influencing

the foundations for the inclusion and exclusion of animals in

Christianities.

But Christianity, in its formalised, official and primarily patriarchal

structure does not take other-than-human animals seriously. The

major theological works of such figures as Thomas Aquinas, John

Calvin and Karl Barth, the central doctrines and creeds of the

both the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches as well as the primary

themes of the Protestant world focus on human beings and the human

relationship with the divine. Humans are of ultimate concern,

with little or no regard for other animals. The culmination of

the anthropocentric model in constructive theology and philosophy,

as well as anthropocentric scriptural exegesis, melded with the

philosophy of the Enlightenment to conclude that a fundamental,

essential, divinely-ordained difference exists between humans

and animals.

[This is in contrast to post-mediæval attitudes

to handicapped children. Mediæval thinkers, notably including

Martin Luther, were convinced that they were changelings and hence

non-human. Thus they could be killed, beaten and tortured without

any sanction from society. Gradually, however, the changeling

legends (which involved fairies, who were fallen male angels who

had by God's mercy escaped Hell, but could not reproduce) came

to be seen as preposterous. For a while Roma people (Gypsies)

- themselves regarded, and still regarded, with the deepest suspicion

- took on the rôle of the child-snatching-and-substituting

Fairies. - A.W.]

Yet various sources tell a different story, reveal a different

image. The artwork, hagiography, oral traditions (later recorded

in written form) and important legends reveal a close connection

between humans and the natural world. Stories and images of animals

abound. I suggest that these animals are not always or only symbolic

or metaphoric but are often subjects, agents in the complete sense.

Images and narratives contain multiple encodings and decodings.

Oftentimes the animals presented in words and images are sacred,

and play an active rôle in the revealing of the holy.

What is the context for animal saints and why, over the course

of the last few centuries, have these stories disappeared ? It

could be argued that most of the examples presented here are stories

of animals with saints, not animals as saints. However,

when one attends to the rôles of the actors, particularly

the active rôles of the animals in these stories, the rôles

are often reversed. Through their agency animals subvert the "power"

and "control" of the human saint and elevate the status

and piety of the animal saint.

Who is the saint or who are the saints in each story? That is

sometimes left to the interpretation of the hearer of the story,

seer of the image or witness to the event. The primary sources

for these stories are the lives of saints from the 2nd century

to the 16th century CE and religious images throughout the Christian

areas of Europe during the same period. The religious imagery

on which the paper, as well as my other work, focuses is popular

art, displayed in churches where masses of common people see and

interpret its meaning. A tracing of these stories and images suggests

that certain patterns reveal cultural continuities and shared

symbols. The four patterns that I address are: animals as exemplars

of piety, animals as sources of revelation, animals as saintly

martyrs, and animals as the primary intimate other in relationship.

Animals as exemplars of piety

Lions abound in Christian legend and symbol. For centuries lions

stood on either side of many bishops' seats in cathedrals and

framed the doors of many churches, including the church in which

the young St. Francis was baptized - San Ruffino in Assisi, Italy.

One of the most amazing lions appears in the Acts of Paul. An

early fragment, in Coptic, tells of a lion approaching Paul as

he prayed. The lion lay down at the apostle's feet and Paul, never

missing an opportunity to convert, asked the lion what he wanted.

The lion replied, "I want to be baptised." Paul

took him to a river and immersed him three times. The lion then

greeted Paul with "Grace be with you!", then

departed into the countryside. Baptism, the Christian sacrament

that confirms an active choice of belief and that initiates one

into the Christian community, is requested by and granted to a

lion.

Lions also provide protection for Thekla, a companion of Paul

in his journeys. At her martyrdom the beasts which were to tear

her to pieces were exhibited. Then she was bound to a fierce lioness...And

the lioness, with Thekla sitting upon her, licked her feet; and

all the multitude was astonished...And Thekla...was stripped and

received a girdle and was thrown into the arena. And lions and

bears were let loose upon her. And a fierce lioness ran up and

lay down at her feet...

A series of animals, some of whom meet their own demise, encounter

Thekla during the numerous attempts to execute her. Eventually

the lioness dies protecting her. One question, based on Paul's

choice to baptise a lion by water, is whether the lioness who

dies defending Thekla earns actual martyr status.

And what about

the inclusion of animals in other central Christian sacraments,

particularly the Eucharist? Apparently, animals have been invited

to partake in this ritual as well. In Donatello's image, the scene

is the celebration of the Eucharist, the central act of many forms

of Christian worship, and of a mule kneeling before the host,

the body and blood of Christ.

Saint Antony of Padua, considered to be the greatest preacher

of his time, was a young Franciscan who preached to fish much

as his predecessor, Saint Francis, preached to the birds. The

miracle of the mule suggests the incorporation of animals into

both the liturgy and the sacramental life of the Church. The image

appears in highly acclaimed works of art, such as Donatello's

bronze sculpture in a church in Padua, and on the walls of baptisteries

frequented by the most common of people, such as the Baptistery

in Siena.

A similar pattern is revealed throughout the stories of the life

of St. Francis of Assisi. Many animals are connected with him,

and the many artistic renderings of his life include birds, wolves

and donkeys in company with the saint. Even images of Francis

in ecstasy, at the height of mystical union with the divine, include

animals. But a particularly poignant tale reveals the piety of

the birds: "As St. Francis spoke these words to them,

all those birds began to open their beaks, and to stretch out

their necks, and to open their wings, and reverently to bow their

heads to the ground, and to show by their motions and by their

songs that the holy father had given them very great delight.

St. Francis rejoiced with them and was glad and marvelled much

at so great a multitude of birds, and at their most beautiful

diversity, and at their attentiveness and fearlessness, for which

he devoutly praised the Creator in them."

An "infinite multitude" of birds, [Francis addresses

them as "little sisters"]

gather and attentively listen to Francis as he preaches about

their blessedness and their need to praise God. ccording to two

of Francis's biographers, he "blessed them, and having

made the sign of the cross, gave them leave to fly away to another

place...nor did one of them move from the spot until he made the

sign of the cross over them and gave them leave." Upon

leaving, another symbol of piety emerges as "all those

birds soared up into the air with wondrous songs and then divided

themselves into four parts after the form of the cross Saint Francis

had made over them." The birds then proceed to announce

their own belief: One flock flew toward the East, and one toward

the West, and one toward the South and the fourth toward the North.

And each flock went singing marvellous songs.

One of the primary scenes attesting to animals as exemplars of

piety is also one of the most powerful symbolic-visual sets of

images in Christian history stories of the nativity of Jesus.

These stories include images of adoring animals surrounding the

manger. Cattle, sheep donkeys and the occasional dog or horse,

prove uncanny in their ability to recognize the revelation of

incarnation of the nativity. Indeed, some images depict humans

as much less aware of the nature of the incarnation than were

the animals.

Animals as sources of revelation

Animals have also been direct sources of revelation-messengers

of the divine to human beings. Most particularly, animals have

been the bearers or carriers, of the incarnation of the sacred

- the bearers of Christ.

While hunting one day, a Roman soldier, Placidus, came upon a

herd of deer. One of these, a large stag, impressed the soldier

with his incredible size and beauty. As the stag ran into the

dense woods, the soldier approached pondering how to capture this

animal. Suddenly he noticed a cross with the image of Jesus between

the antlers of the deer. The voice of the divine came from the

stag's mouth and said: "O Placidus, why are you pursuing

me? For your sake I have appeared to you in this animal. I am

the Christ, whom you worship without knowing it. I have come,

that through this deer which you hunted, I myself might hunt you."

The next morning, the vision appeared to him, again with the stag

as the vehicle for revelation. The soldier changes his name to

Eustace and becomes a Christian.

His hagiography relates yet another animal saint. Years later

when Eustace was displayed in the arena for martyrdom, a ferocious

- and very hungry - lion served as the imperial death weapon of

choice. But the lion came out peacefully, lowered his head and

adored the soon-to-be martyrs rather than kill them. There are

other similar stories.

St. Francis Xavier recounted (or invented) his own peculiar animal-aided

vision of the divine. During a mighty storm in the Moluccas, Xavier

tried to calm the waves by holding his crucifix over them, but

a huge wave swept it overboard. Once safely on shore, Francis

saw a large crab coming towards him, carrying the cross in his

pincers.

Animals as martyrs and servants

The most striking images of animals in the hagiography are those

of animals as martyrs or servants.. Following the example set

by Jesus, martyrs claimed a second and ultimate baptism in blood.

Their stories were told throughout Christianities to strengthen

the commitments of believers facing oppression. But some of these

martyrs are, not just symbolically, but literally sacrificial

lambs.

One of the most fascinating martyr-saints is Saint

Guinefort. The stories of his heroic martyrdom (above)

and of the healings that took place at his shrine influenced generations

of believers in Southern France.

In the year 406, Paulinus, a monk and a priest, read a poem honouring

St. Felix on his birthday. The poem features animals as the principal

characters in a series of miracle tales. Christianity had denounced

animal sacrifice, primarily as a sign of differentiation from

Roman religious systems. But the rituals continued, particularly

in rural areas. At the tomb of St. Felix, in southern Italy, the

practice had been Christianized and served as a way to distribute

food to the poor who would gather at the tomb to collect meat

from the sacrificed animals.

The first tale is of a horse "seemingly endowed with human

reason" who provided a "holy sign" and became a

"source of wonder for those in attendance." This inspired

horse intervened as his master attempted to take the best portions

of a hog that he had sacrificed rather than leave them for the

poor. The equine saint threw the greedy man to the ground and

then carried the sacrifice back to the tomb. Power and compassion

are central to this horse-saint's piety.

A second story comes from this same tradition and relates the

miracle of a rather plump pig. She had been vowed to Felix at

birth, but because of her girth she was unable to walk the distance

to the shrine. Her masters took two smaller piglets in her place,

but when they arrived, the pudgy pig was already on the altar

offering herself as sacrifice. Obviously, the sacred had been

revealed in and through the pig who, by some accounts, placed

her throat on the blade, willingly offering her life as food that

others might live.

A similar story tells of a heifer who walks without a halter to

the altar and "undefiled by the yoke and offering its

neck to the axe, about to provide food for the poor from its slaughtered

body, joyously it poured out its blood in fulfilment of its masters'

vows."

Parallels between the sacrificial rôle of these animals

and that of the figure of Jesus, particularly in their theological

connotations, prove both striking and potentially controversial.

Of course, the lamb is a pervasive visual and liturgical symbol

of sacrifice and piety, oftentimes replacing the figure of Jesus

and other disciples. A beautiful example is the seventh century

apse of Sant' Apollinare in Classe that portrays all of the twelve

traditional disciples as sheep.

So the symbol of the animal as sacrificial victim and even as

saviour is central to Christianity. But the stories of St. Felix

move these animals into active rôles, symbolic and actual

in their life of sacrifice.

Another common theme of animals as servants comes at the time

of death and burial. A story similar to that of Saints Paul and

Anthony tells of another lion assisting in the burial of a saint.

St. Mary of Egypt, a hermit and ascetic, had lived in the desert

for years, eating only bread and lentils. A monk, Zosimus, came

across this figure of holiness as he traversed the desert. One

year, he served her the Eucharist and promised to bring this sacrament

to her the next year as well. When he came back, he found her

dead. Zosimus tried to dig a grave but could not. Then he saw

a lion meekly coming toward him and said to the lion: "This

holy woman commanded me to bury her body here, but I am old and

cannot dig, and anyway I have no spade. If you could do the digging

we will be able to bury this holy body together."

The lion began to dig and prepared a suitable grave, and when

that was finished went away "like a gentle "lamb.

Even arachnids seem to hear the voice of God without hesitation

- for another story connected to a saint named Felix includes

spiders as heroes. While preaching, Felix, a bishop, found himself

being pursued by persecutors, so he proceeded to hide:...he slipped

through a narrow opening in the wall of a ruined house and hid

inside. In a trice, by God's command, spiders spun a web across

the space. The pursuers, seeing the web, thought that no one could

have gone through the opening, and went on their way. Later Felix

was killed by a group of boys he taught. Boys can be less compassionate

even than spiders.

Animals as primary other in relationship to humans

Finally, there are numerous stories of animals as the primary

other in relationship to humans throughout the Christian tradition.

Obviously many of the hermits and desert dwellers mentioned throughout

are in the company of an animal or animals. In addition, anchoresses

who lived cloistered, often as solitaries, would be permitted

one cat in their cell. But one of the most popular stories of

saint-animal companionship is that of St. Jerome, a Father of

the Church who lived in the wilderness, probably close to Bethlehem,

while translating the Bible from Greek into Latin. He lived with

some other monks, and many animals including dogs ,hens, sheep

and donkeys.

One day, a great lion came into

the monastery courtyard. Needless to say, all the monks scattered,

except for Jerome. He noticed that the lion was limping and welcomed

him in the spirit of hospitality that pervades most monasteries.

Jerome healed the lion, who decided to remain with Jerome.

The adventures of Jerome and the lion continue, but suffice it

to say that on the death of the saint, the lion, a saint in his

own right,is said to have grieved without ceasing.

This is not the only such account. The story of St. Giles and

the hind is tender and tragic. Giles, who had cured many, became

a solitary living in a cave close to a beautiful spring. But he

was only a solitary in terms of his relationship with people,

because as the story goes "for sometime he was nourished

with the milk of a hind" or doe. Eventually, a group of hunters

pursued her and she took refuge with St. Giles in his cave. She

was "whining and whimpering ... not at all like her"

so Giles went out and, hearing the hunt, prayed that God would

save this doe, the "nurse" whom God had provided. This

happened again and again, until finally, on the third day, the

king brought a bishop along with him to survey the situation.

This time "one of the huntsmen shot an arrow into the cave,"

wounding St. Giles as he knelt in prayer for the life of the doe.

St. Blaise, a bishop, also decided

to live the life of a hermit. He "retired to a cave"

where "birds brought him food, and wild animals flocked to

him." These animals would not leave "until he had laid

hands on them in blessing." This action indicates that Blaise

understood the animals worthy of blessing and the animals understood

the significance of the ritual. In addition, Blaise offered them

healing and "if any of them were ailing, they came straight

to him and went away cured."

Conclusions

Can animals be counted among the

saints in Christianity? They have served as the locus for revelation,

been examples of piety, offered themselves as martyrs and servants,

and, in their relationships with others, have been the source

of agape - divine love. Thus, the sacred history, though often

obscured, suggests that animals may indeed be counted among the

holy ones in the Christian tradition.

Of course, the functional world-view

for these animal-human-divine relationships reveals a significantly

different historical context in many cases. Humans and animals

were intimately related in everyday life during the periods when

these stories were developed. In contrast Euro-American culture

of the early twenty-first century is a culture alienated from

the natural world and other animals in most manifestations. Popular

images of animals have morphed into human projections on a vast

scale-from Disney's mawkish sentimentalities such as Bambi

or The Lion King, to cultic-pornographic pedigree dog

shows, to mass produced flesh for food, with the actual dead animal

being an utterly-absent referent.

These differences could, arguably, render the relevance of such

animal stories impotent. But even in those different cultural

contexts saints provided an alternative relationship. Andrew Linzey,

one of the few contemporary theologians to address the issue of

animals, suggests this possibility in his book Animal Theology:

"We need to remember that the challenge of so many saints

in their love and concern for even the most hated of animals,

was in almost all cases against the spirit of their times..."

|

AN

ISLAMIC VIEW

from "How

to become Holy"

written in 1453 by Abu Abdallah

Muhammad Al-Jazuli Al-Simlali.

In

order to eliminate feelings of self-importance, he who would become

holy would do well to acquire the Ten

Praiseworthy Attributes of the Dog:

1. He sleeps only a little

at night; this is a sign of the God-lover.

2. He complains of neither

heat nor cold; this is a sign of patient endurance.

3. When he dies, he leaves

nothing behind to be disposed of; this is a sign of asceticism.

4. He is neither angry nor

hateful; this is a quality of the faithful.

5. He is not sorrowful at the

loss of a close relative, nor does he accept assistance; this

is an attribute of the unshakeable.

6. If he is given something,

he consumes it and is happy; this is a sign of the never-demanding.

7. He has no known place of

refuge; this is the quality of holy wandering.

8. He sleeps in any place that

he finds; this is a quality of the never-complaining.

9. He is incapable of hate,

even if his owner beats or starves him; this is a quality of

the knowers of wisdom. (Compare the injunction

in the Hindu Upanishads: "Be like the sandalwood that

perfumes the axe that hacks it.")

10. He is always hungry, which

is a sign of the virtuous.

These attributes were amongst those of the black (therefore despised)

Moroccan saint, Abu

Yi'zza.

|

Rejoice

in the Dog >>

The

Parable of Lazarus >>

Saint

Onouphrius of the Desert >>

An

Albanian Ikon >>

The

Nature of Christianity >>

more

on Cynocephaly >>

This web-page is dedicated to the memory of Saint

Oscar the Curly-tailed.

|

![]()